L’exposition “Garb-age” des MURMURE dans Juxtapoz, 04/03/20

https://sortir.telerama.fr/evenements/expos/quentin-garel-anomal,n6587298.php

On aime passionnément

Quentin Garel ne pouvait rêver plus bel écrin pour ses sculptures animalières que le domaine de Chamarande ! Le château lui offre le décor idéal d’un cabinet de curiosités. L’artiste, dont on a déjà pu voir les œuvres en 2016 au Muséum d’histoire naturelle, laisse s’échapper ses créatures dans les salons, environnées de grandes esquisses – superbes ! Têtes de girafe ou d’autruche, mâchoire de crocodile ou pièce de squelette, l’œil est constamment aux aguets, ne sachant s’il est confronté à la réalité ou bien à une vision fantasmée. Peu importe, l’œuvre est stupéfiante, inclassable ! Une visite à prolonger absolument dans le parc.

Bénédicte Philippe (B.P.)

A Review of Rithika Merchant: Mirror of the Mind at Galerie LJ, Paris

Courtesy of Galerie LJ, Paris – © Vogue Magazine and Carlos Teixeira.

For a first solo show, it’s hard to beat exhibiting in the heart of Paris. A stone’s throw from Le Centre Pompidou sits the avant-garde Galerie LJ, known amongst Parisians for its investment in chic emerging artists. Rithika Merchant is no exception. Having exploded onto the international scene in 2018, thanks to her collaboration with the French fashion house Chloé, Merchant’s work has become the object of consistent media attention. Most notably, earning the young artist Vogue’s title of Young Achiever of the Year in 2018.

While Merchant currently lives and works in the vibrant city of Barcelona, she was born in Mumbai, India and was subsequently educated at Parsons in New York City; as well as The Hellenic International Studies In The Arts on the island of Paros, Greece. Given her many colourful homes, Merchant posses a unique cosmopolitan worldview that is detectable in her now recognisable oeuvre. A delectable mixture of Eastern and Western motifs that intermingle with the themes of spirituality, mortality and heritage; Merchant’s best pieces are hybridised treasures that read as both familiar and foreign.

Rithika Merchant, Divine Bodhi 2017, print collaboration for Chloé SS18.

One of the most distinctive elements of Merchant’s work is her choice of medium. While many young contemporary artists favour the staples of acrylic and oil, or are introducing digital elements, Merchant has chosen to work with collage and primarily with gouache and ink on stained paper. A quick history lesson: this technique reaches as far back as ancient Egypt and Greece (consistent with Merchant’s Hellenistic education) and often produces a flat, muted colour palette reminiscent of Indian miniature paintings. Despite being revived by the Impressionists in the nineteenth century, the technique is still only the preference of a select few. Such a distinct choice immediately piqued my interest, as it is noticeably unusual and yet aligns seamlessly with Merchant’s penchant for incorporating mythological symbols – a nod to aeons gone by.

Upon closer inspection, Merchant’s first solo exhibition, Mirror of the Mind at Galerie LJ, features an array of works which share overlapping motifs and compositional similarities. Her reoccurring repertoire of symbols include the evil eye, horoscopic skies, snowy mountain peaks, botanical imagery (the lotus most often), references to palmistry, strong geometric forms (particularly red circles and semi-circles), snakes and large birds of prey. Many of these can also be found in her compositions for the folklore-inspired Chloé collaboration, suggesting Merchant is steadily charting her own unique visual language.

Rithika Merchant, Diffusion 2019, courtesy of Galerie LJ, Paris.

While Merchant has undoubtedly achieved much success through her relationship with Chloé, Mirror of the Mind represents a shift away from the mainstream media and fashion, towards the formalised art world as a whole. Unlike Jeff Koons, who earned notoriety within the art world before embarking on his lucrative fashion collaboration with Louis Vuitton, Merchant is attempting to reverse engineer Koon’s model. A lofty mission that will surely raise the eyebrows of detractors, but one I believe she may very well accomplish.

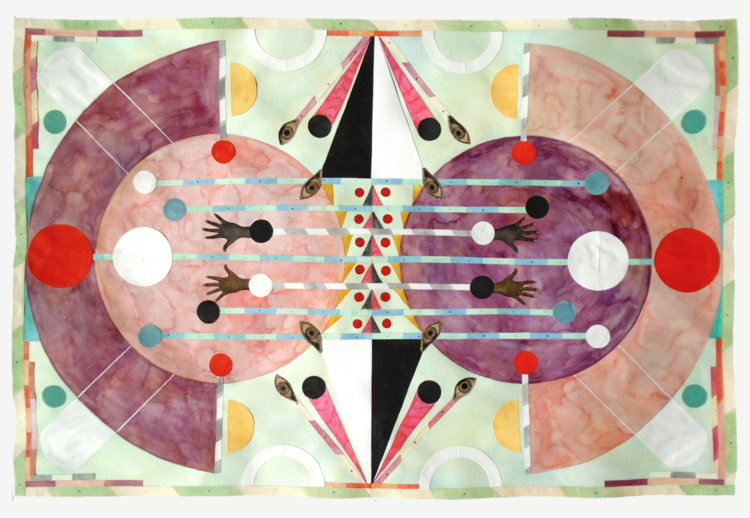

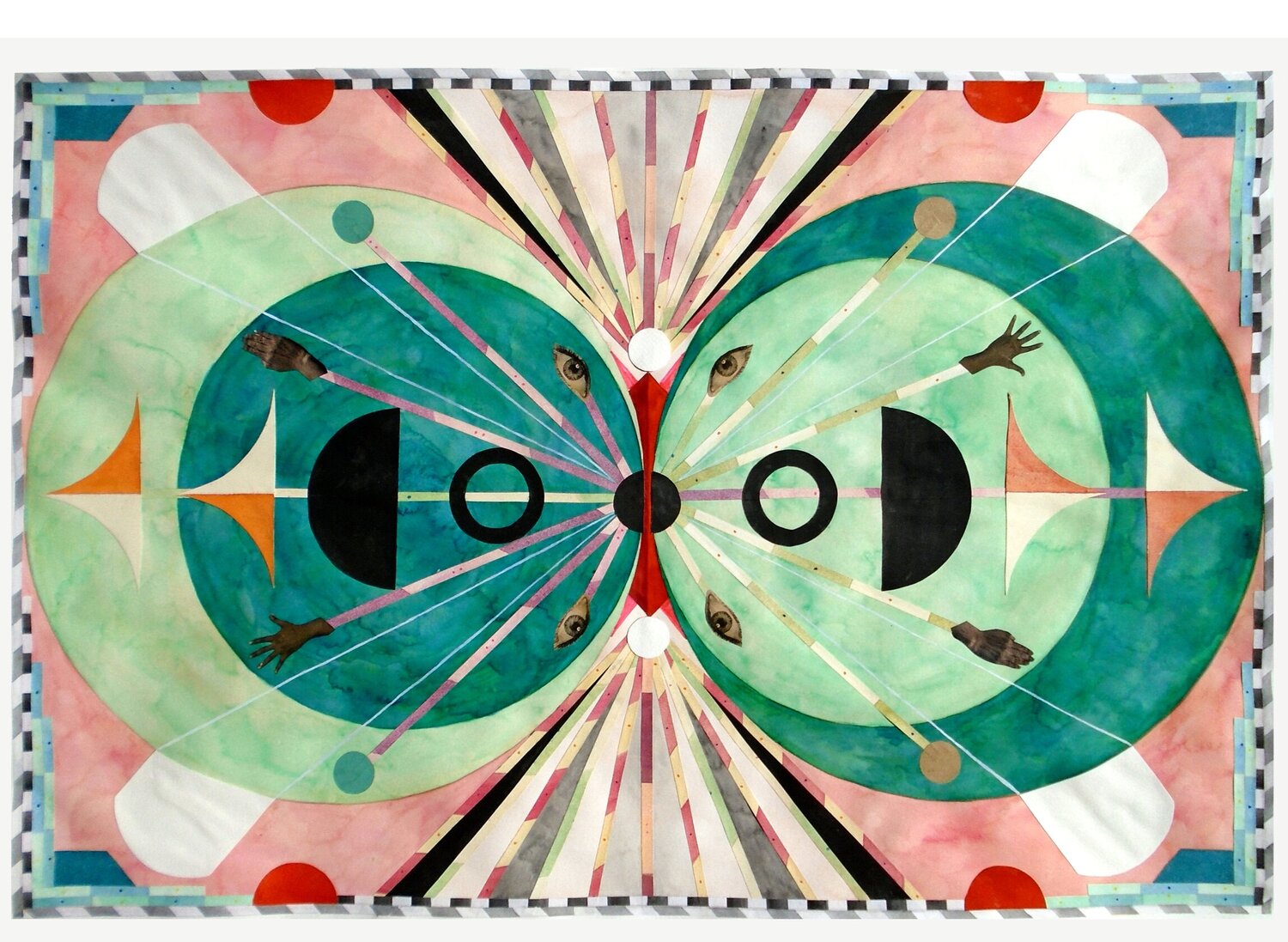

As a first solo show, Mirror of the Mind is impressive in the number of works and the sheer detailed nature of each piece, however; there is a discernible ‘greenness’ to the collection – a subtle disconnect in the selection of works. In my estimation, the body of work can be divided into two groups – cleanly composed mirror images (where if I drew a line down the centre of the image, each side would mirror the other) and narrative scenes that edge towards the overly illustrative. The ‘mirrored images,’ which include Nazarbattu (2019), Diffusion (2019) and Memory Tree (2019) are, in my opinion, the strongest works due to their balanced composition and the much-needed inclusion of negative space.

Rithika Merchant, Nazarbattu 2019, courtesy of Galerie LJ, Paris.

In her ‘mirrored images,’ Merchant demonstrates the invaluable ability to edit her compositions in favour of legibility and a more poignant visual impact. The works, while simpler than some of their counterparts, more fully communicate Merchant’s worldly artistic influences and allow her incredible details to be fully digested. By contrast, some of the narrative images feel more akin to the illustrations found in Maurice Sendak’s famed children’s book Where the Wild Things Are. Clearly, we are witnessing Merchant experimenting and flexing her muscles as a stand-alone artist, with her forward path yet to be determined.

Merchant herself seems to be a touchpoint for the intermingling of various cultures and industries. India and Greece, Fashion and Fine Art, she cleverly highlights connections that are too often overlooked. A reminder of the fluidity of culture, Merchant’s mystic collages and inky netherworlds will continue to captivate, especially if executed judiciously.

Rithika Merchant, Memory Tree 2019, courtesy of Galerie LJ, Paris.

Written by Maya Asha McDonald,Editorial Director and Contributor to Arteviste

https://www.clovemagazine.com/journal/2020/1/10/rithika-merchant-mirror-of-the-mind

Rithika Merchant: Mirror of the Mind

Currently displaying in Paris, the artist weaves together symbolic images to tell a universal story

Indian artist Rithika Merchant moved to Lisbon in her 20s for an artist residency. She has now been based in Barcelona for 10 years, still diving her time between there and her native Mumbai, where she is represented by Hena Kapadia’s TARQ gallery.

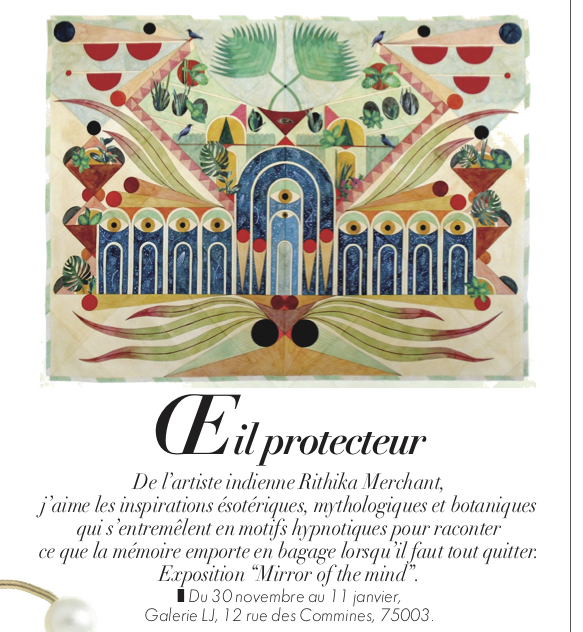

The painter has a distinctive style. Her works are colourful, intricately detailed and heavily two-dimensional – all of which are characteristics of Indian Mogul painting that have long fascinated the artist. For her latest solo exhibition, at Galerie LJ in Paris, Merchant also looked to tribal painting of the Gondi, Meera and Kalighat traditions for inspiration.

Osmosis

Many of these tribal artists have coded ways of leaving signatures on their works – often through symbols or repeated images. “If you’re well versed in these signatures, you can identify the artist from them,” explains Merchant. Similarly, she too employs repeated symbolic imagery as a way of leaving her own imprint on the work and on its viewer.

From the green chillies in the painting Nazarbattu to the multicoloured kite in the Patang, Merchant represents images that recall her Indian ancestry. Objects like these form part of the artist’s exploration of objects as identity markers: “There are so many objects that are passed down through generations that are clues to your lineage,” she says. “In any Indian house you find metal glasses for drinking water – I have glasses just like those in my home in Barcelona.”

Patang

Pachisi

By carrying the memories of such objects across global boundaries, and by representing them in her work, the artist wants to present a universal kind of storytelling, one that crosses borders and is about collective roots. Rather than tying the symbols too closely to one culture, she uses them to weave together several of them – like with the kite in Patanag. Kites are are traditionally flown in certain parts of India during Sankranti, a harvest festival in January – but kite-flying is a strong tradition in many cultures of the world, like China, Merchant explains. It is much the same with mask-making, another frequent motif in Merchant’s paintings.

Nazarbattu

The majority of the works, all of which were specially created for this exhibition, have now been sold – and the buyers have largely been French and European. Despite drawing specifically on her own Indian ancestry when creating art, Merchant feels that is is by tapping into universal ideas and images that her works speak to people from different cultures and backgrounds.

The painting Pachisi, for example,depicts an ancient Indian game by the same name, which is believed to have formed the basis of many games played today the world over, like Ludo. The game board layout of the painting is instantly recognisable and awakens deep and fond memories in the viewer. “I like tapping into these ideas that everyone can relate to,” she says. “It’s interesting to see people recognising something, even though they don’t quite know why.”

Palingenesis

‘Mirror of the Mind’ is at Galerie LJ in Paris until 11 January 2020. Merchant displays this year at India Art Fair, Art Madrid, DDessin Paris, and more.

Swoon’s Surrealist Stop-Motion Films & Installations Take over Jeffrey Deitch NYC

Diverse works that draw inspiration from personal memories and classical mythologies.

https://hypebeast.com/2019/12/swoon-cicada-jeffrey-deitch-nyc-exhibition

Jeffrey Deitch’s 76 Grand Street outpost in New York City is currently hosting a most dynamic exhibition by the famed interdisciplinary artist, Swoon. Entitled “Cicada,” the exhibition features a series of recent animations, drawings, and surrealist installations that are an extension of her wheat-pasted portraits made using found objects. The works on display draw inspiration from her personal experience, classical mythologies, and the craftsmanship of 20th-century folkloric films.

“Swoon’s response to parts of her family history – and the legacy of her parents’ addiction and substance abuse – has recurred throughout her work,” expressed the gallery in a statement. These components inflict a strong element of realism to the films, grounding the otherwise- whimsical atmospheres of Cicada.”

Check out the installation views of “Swoon: Cicada” above and then visit Jeffrey Deitch’s website to learn more. The show is on view until February 1, 2020.

Jeffrey Deitch

76 Grand St.

New York, NY 10013

Email hello@galerielj.com

Tel +33 (0) 1 72 38 44 47

Adresse

32 bd du Général Jean Simon

75013 Paris, France

M(14) BNF

RER (C) BNF

T(3a) Avenue de France

Horaires d'ouverture

Du mardi au samedi

De 11h à 18h30