“HOW STREET ARTIST SWOON CREATES LIFE-SIZE DREAMLIKE WORLDS” on The Verge Magazine

By Grayson Blackmon, May 17, 2019

https://www.theverge.com/2019/5/17/18627720/swoon-artist-caledonia-curry-submerged-motherlands-art-club

Every week, The Verge’s designers, photographers, and illustrators gather to share the work of artists who inspire us. Now we’re turning our Art Club into an interview series in which we catch up with the artists and designers we admire and find out what drives them.

In 2014 when I first moved to New York, I visited the Brooklyn Museum and saw the exhibit Submerged Motherlands. It was a dreamlike, larger-than-life experience created by the artist Swoon, who first gained notoriety in the early 2000s as a street artist. The intense detail and scale of every piece astounded me, and I’ve been following her work ever since.

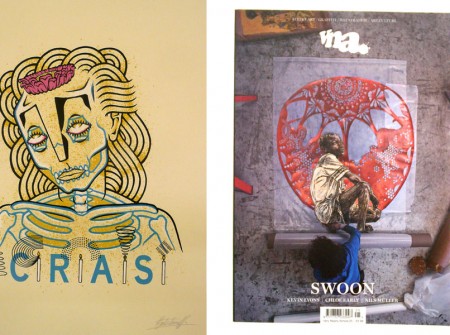

Swoon, born Caledonia Curry, has been experimenting and challenging herself for almost 20 years. Since studying at Pratt Institute, she’s been creating massive installations for galleries as well as engaging in humanitarian efforts. Her work with the Konbit Shelter in Haiti after the 2010 earthquake helped create a sustainable community center and single-family houses in Cormier, Haiti.

Swoon invited me into her studio space in Brooklyn to talk about the link between street art and studio work, the messy process of drawing, and taking her artwork out to sea.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/16275006/akrales_190509_3391_0147.jpg)

What was the transition from street artist to studio artist like?

I always had a studio practice, since I was a little kid. I studied classical painting, and even when I was doing work that was really made to live out in the street, most of the time making it was spent in my studio. So the real question was just around, “where does the art live?” At first I was like, “I don’t want to just make a square that goes over a couch.” And now, I’ve gotten to the place where I’ve threaded through so many layers of meaning and life into my work that I’m okay if one aspect of it is also a square over a couch. Like this is a portrait that’s part of a larger process, and if there’s a piece of it you can keep, that’s awesome.

I actually prefer that to only having things disappear. It’s nice to have a dual trajectory. So the studio process was always there, it was really more about the transition from street to gallery museum. At the time when I first got asked to do that, it was like, “Okay, does this really make sense? Is this right for me?” And then as you saw at the Brooklyn Museum, we had this 70-foot tree that was guy-wired into the building. Now you could see them up close, whereas they had just been on the water before. So what I found is that there are certain things that can happen in those protected spaces.

Do you plan to do any more street art?

Right now I’m taking a break because [with] every piece I was making, I was always thinking that it had to live out in the street. It was starting to dictate what I was making in a certain way and I was like, “You know what? If I’m going to really evolve creatively, I have to actually pause some of the things that are my known go-tos, so that I can surprise myself a little bit.” Like I have to stop doing certain things that are comfortable in order to get uncomfortable, which is that really creative space.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/16274996/akrales_190509_3391_0047.jpg)

What piece are you most proud of?

The piece that I’m most proud of right now is this piece called the Medea. It did something that no work of art that I’ve ever made has ever done. I was able to start with a psychological state that I myself was in, which was kind of like a cognitive, dissociative, like fragmented place that was related to memory and childhood trauma and all kinds of things.

And then I was able to — through the creation of the piece to make physical the process of fragmentation of the mind — to braid it back together and to bring it back into cohesion. I know that sounds really abstract and complicated, but it’s one of those things where you’re like, “Oh fuck, this is what a work of art can do.” It can let you do these things which feel really abstract and complicated and a bit nebulous, but sort of concretizes them. There’s what your brain is doing and there’s what your hand is doing, and then bringing in stories, drawings, myths, and all different kinds of things. Somehow it allows a little bit of alchemy to happen.

Who’s been your biggest inspiration?

I love this nun named Pema Chödrön.She’s a Buddhist nun and she is really quite remarkable in that she’s able to study Buddhism, get into the depth of the whole Buddhist canon and then to translate it into completely ordinary terms. I feel like where I’m at as an artist right now is kind of drilling down into the human experience and drilling down into consciousness itself. Nobody does that better than the Buddhists. I’ve just binge-listened to almost everything, plus I read The Places That Scare You and I just love her. She got me meditating. I meditate daily, I do like 10-day retreats every year.

Can you take me through the process of creating one of your portraits?

It depends on the specific portrait. Sometimes I just catch something candidly. I don’t do any digital transfer, I just draw from the photograph. I found that if I don’t just draw it freehand, it won’t be wrong enough to feel like my drawing.

Like if I lay it out and just copy it, it’s a little too like everyone else who lays it out and copies it. But when I do my own drawing, there is something that I never quite get right and that becomes the style of why you recognize that that’s my piece. I just believe in the dedicated act of looking that happens when you just try and try again to draw someone’s face, and you erase it, and you try again, and you look deeper and you struggle with that. I just feel like that is why we are making drawings in the first place rather than taking a video or taking a photograph. Like that’s why drawers draw. That’s why I draw.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/16275015/akrales_190509_3391_0125.jpg)

After you start that process, what’s the actual physical process to getting it blown up?

Well all the block prints, that’s their scale. So I roll out the linoleum and then I draw with charcoal on the linoleum, and then I solidify the drawing with ink so that I know exactly where I’m carving. And then once I start carving, I almost shut my brain and put on a Pema Chödrön book or whoever, and just get in the zone of carving while the decisions have been made. And then [after you] print it out, you have to kind of go back and wrestle the drawing back out of the print. Lately, I’ve started doing silkscreens from the drawings because I’m starting to stop some of my processes, so that I can learn new things like stop-motion animation.

So the installation like Submerged Motherlands, how long did that take you to put together?

So long. Yeah, that was at least six months. And, in fact, more because you saw there were two rafts in the project and those had been built years before. So the tree, the temple, a lot of those drawings had been coming into fruition for like a decade. It took six months to get it prefabricated and get it put up. But to really examine the labor that went into it, I would say it took like a decade.

Talking about the boats, what was it like making a piece of art that floats? Were you scared at all the first time you rode it?

Yeah. I mean it was really astonishing in this way where, we did it, we built it. But still the feeling of being out on it floating, you were like, “Are you fucking kidding me?” And driving it? You’re like, “Oh my god, I am driving my art at sea.” Just a wild feeling. Also like stepping away, like getting on the little skiff and driving out and seeing it. The first time that happened I was like, “Are you fucking kidding me, that’s what we did?” Like even I had been doing it for months. Seeing it be alive on water was just totally mind blowing.

Jumping back to what you were saying about exploring techniques, what are you currently obsessed with technique-wise or style-wise?

Well, I’m obsessed with learning moving storytelling. I’m not working with narratives so much as I’m starting with an image and letting a narrative build out of the image. But what I’m finding is that as soon as you introduce time, everything is a story in a way. Like you’re a motion graphics person, you probably know that. That there’s this funny magic that happens where once you expand in time, it’s like a whole other ballgame.

Because I’ve worked in narrative drawings for so long, I’m finding that the transition is completely natural. And I feel like a little kid in this way, like, “Oh my god, this is so fun.” Playing with it and seeing where it goes is what I’m obsessed with right now.

I’m definitely always trying to learn some kind of new technique or something. That’s my favorite part of the job when you don’t know how to do something.

That’s exactly why I had to put down a bunch of my processes because I didn’t have enough time doing things I was confused about.

I definitely feel like when I’ve worked on something for so long, it’s so muscle memory. It’s like, why am I doing this?

Yeah, it can become great, but yeah, then there’s a point in which you have to put it down or change or come back to it when you’ve learned something else.

So, what’s next?

I’m going into seclusion for the summer to work on more stop-motion. I have a really hard time doing that in New York and so I’ve been living for part of the year in rural Panama and that’s where I do my film work. I have a feeling that I’m going to start around this experience that I had when my mom passed away. I had something that’s called a shared death experience which is quite strange and a bit mystical. When I learned that it wasn’t just me who had that experience, I was really stoked about that. I have long thought about how to express that experience and so I might take a crack at doing that in film.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/16274997/akrales_190509_3391_0097.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/16275010/akrales_190509_3391_0157.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/16274995/akrales_190509_3391_0001.jpg)