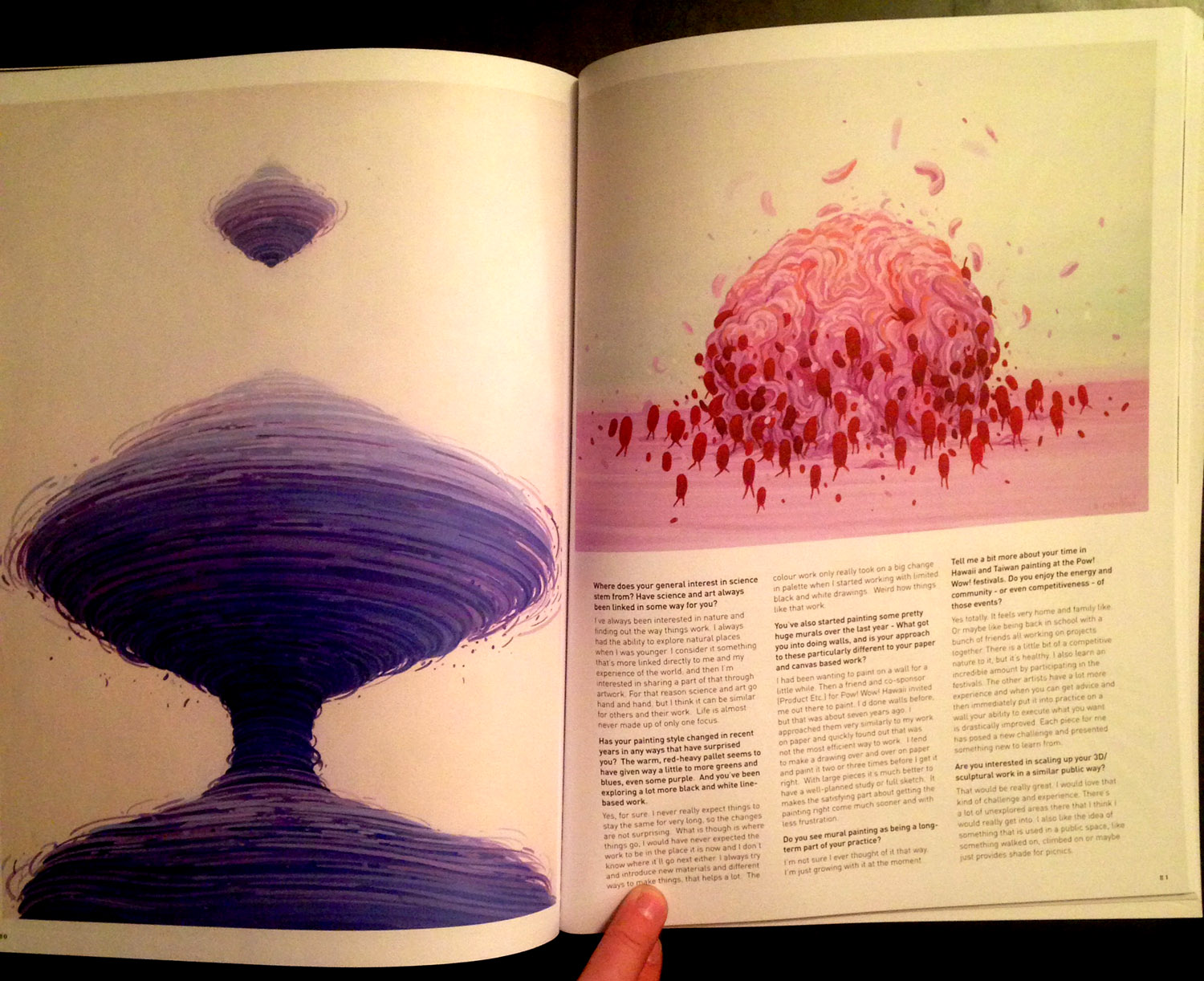

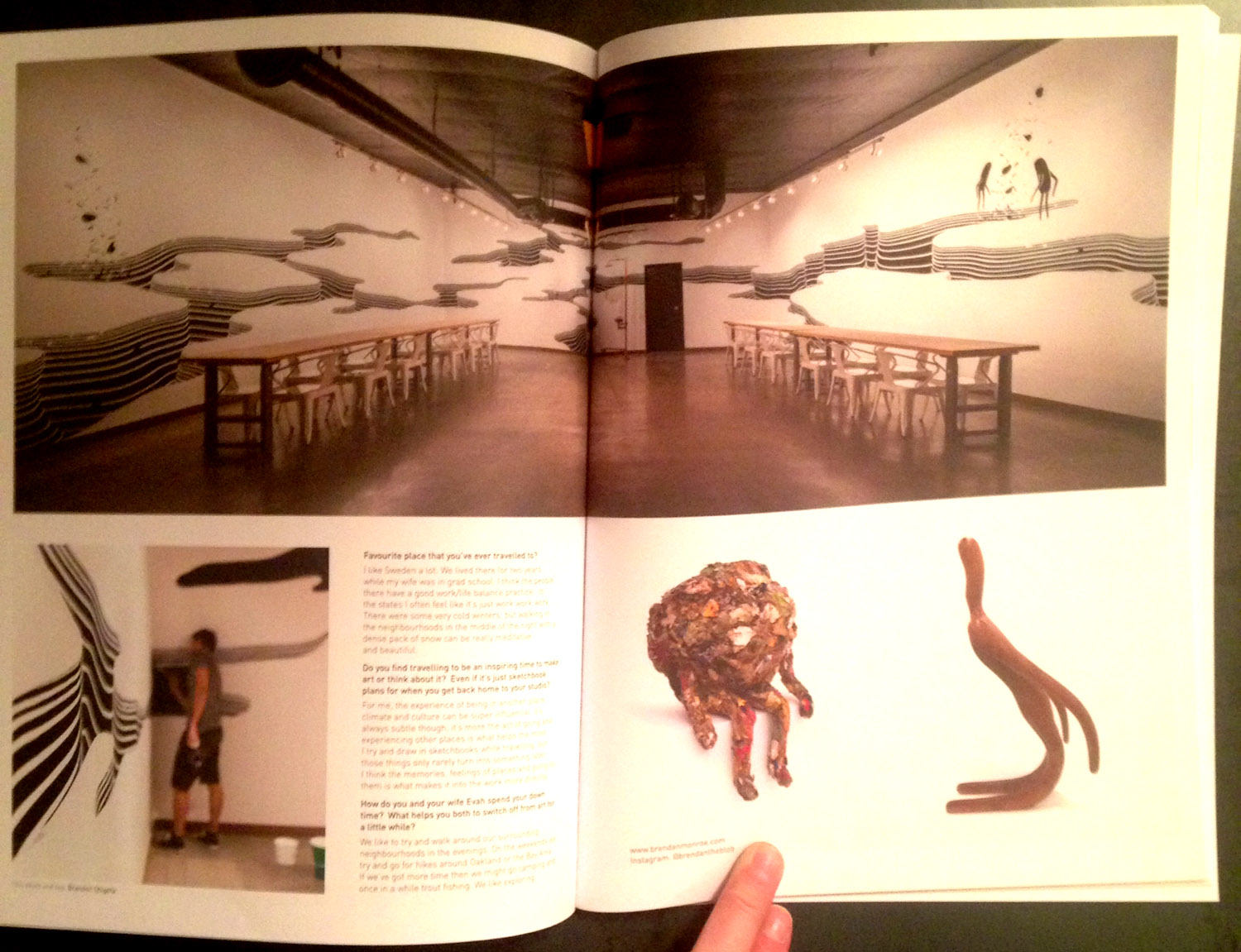

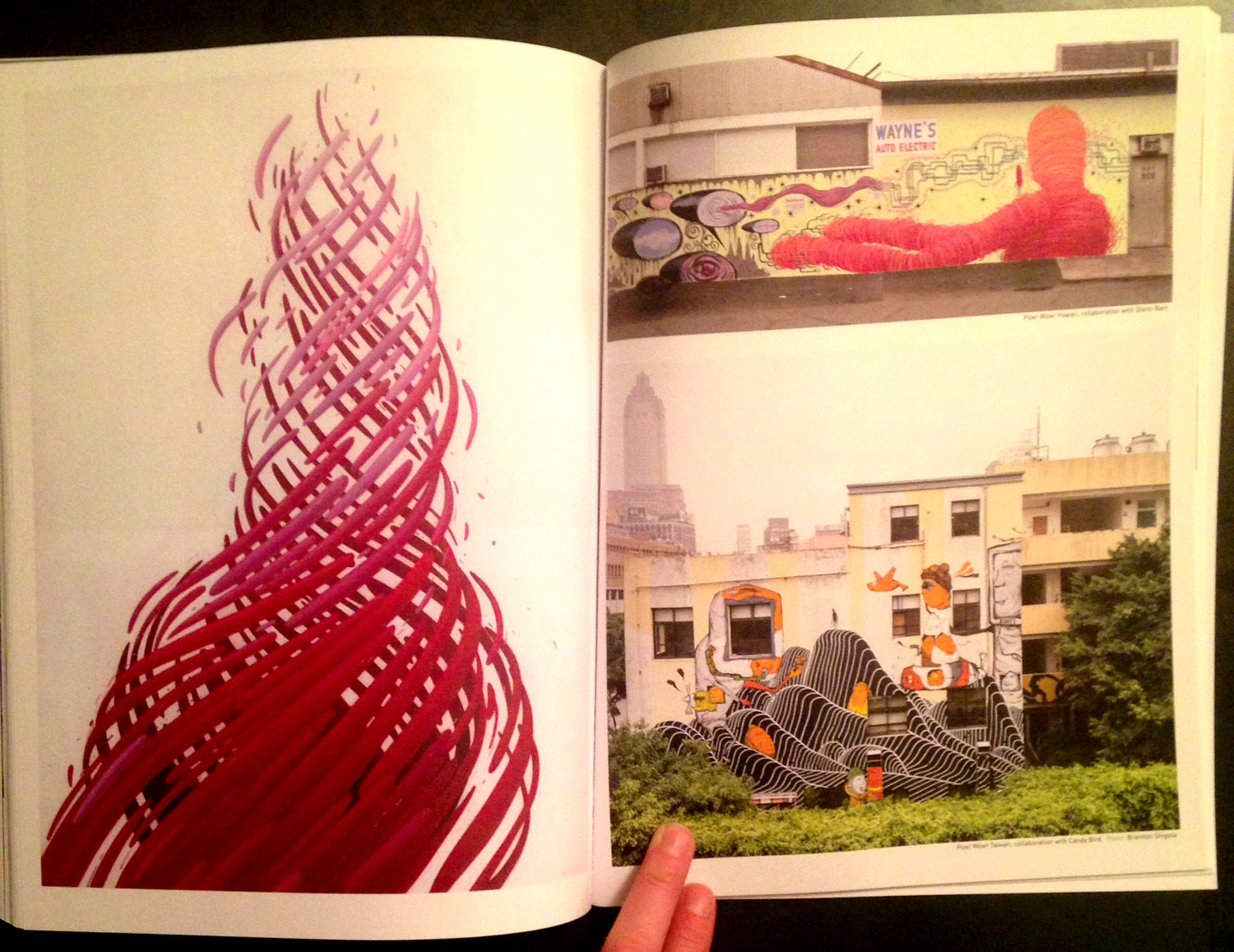

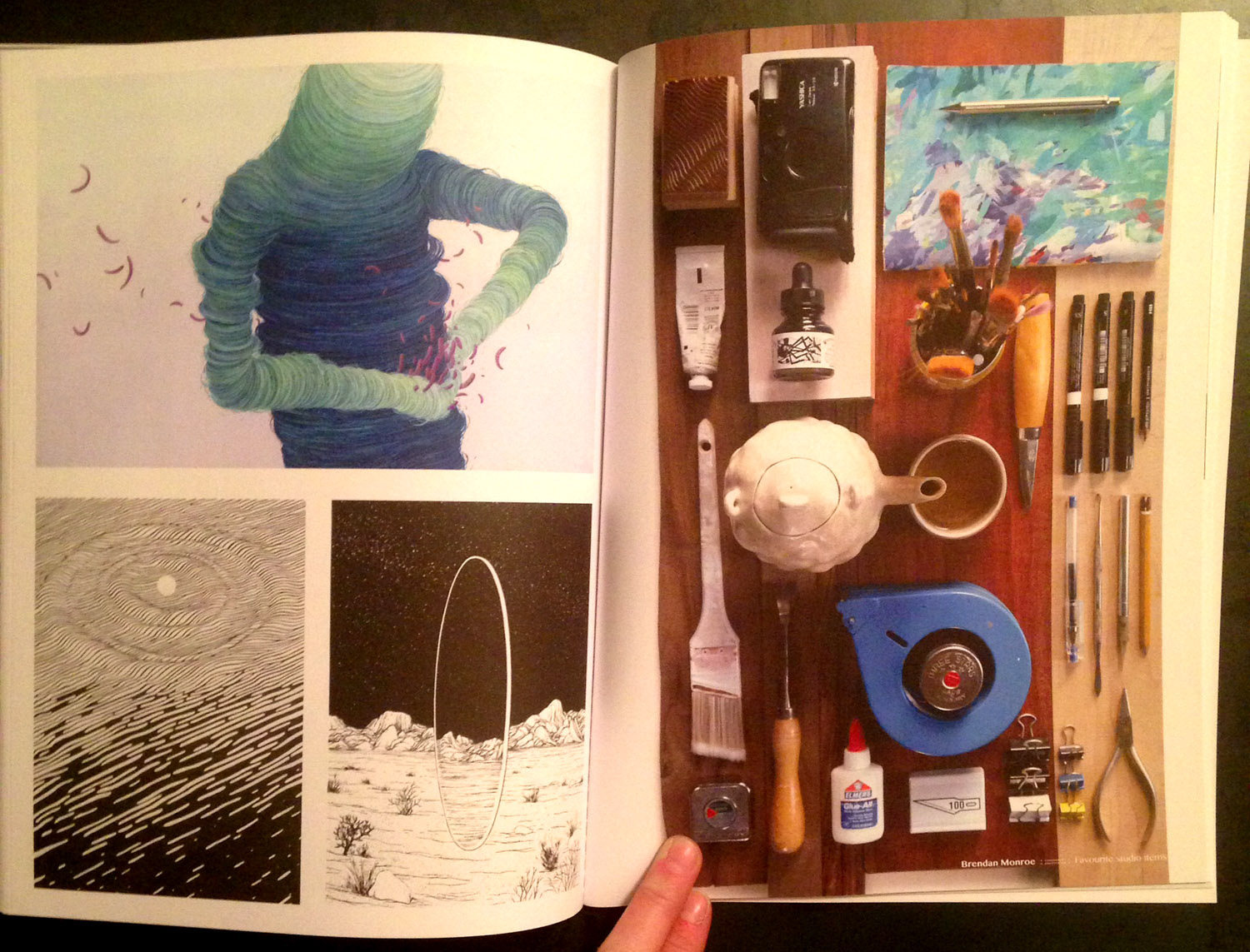

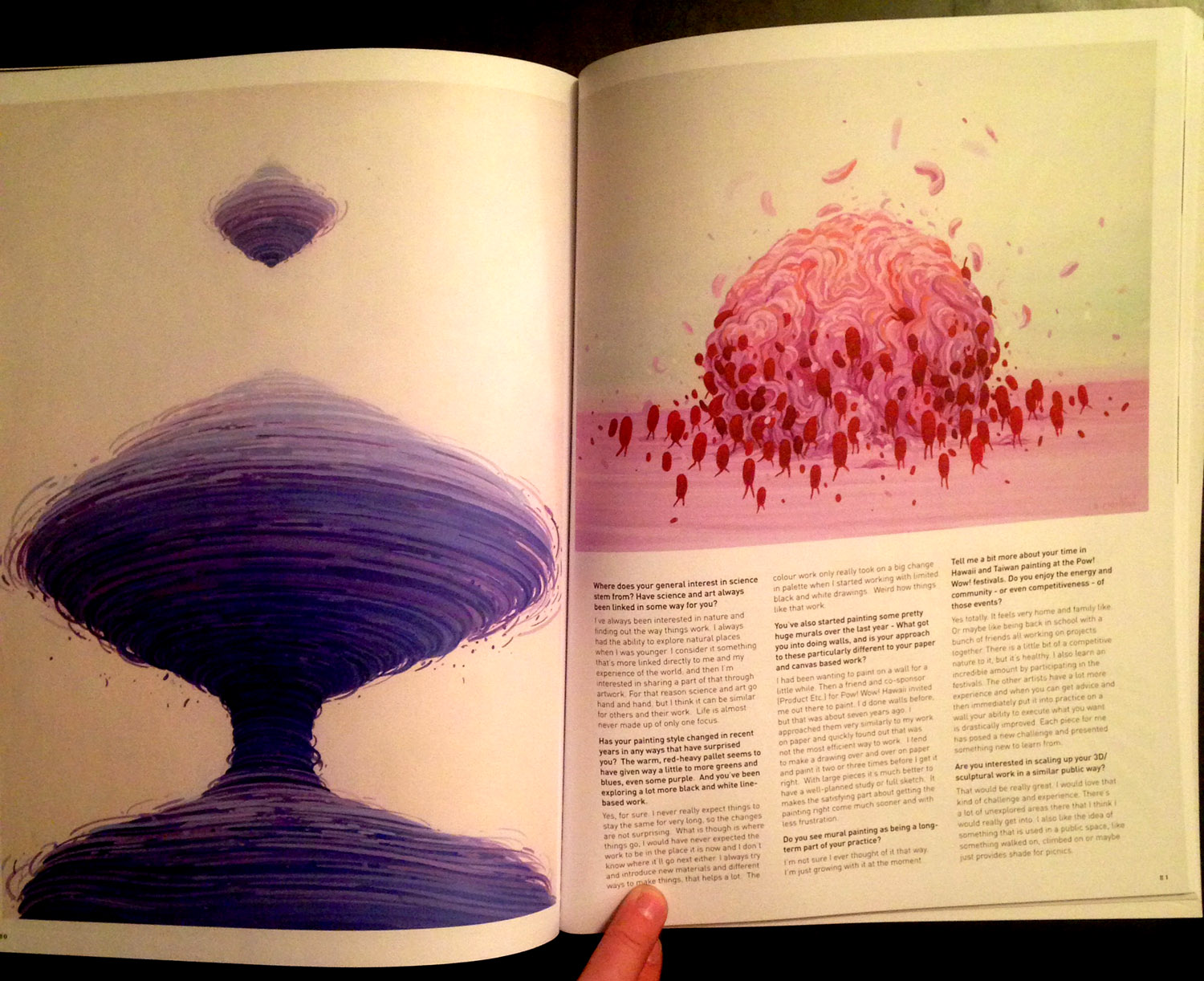

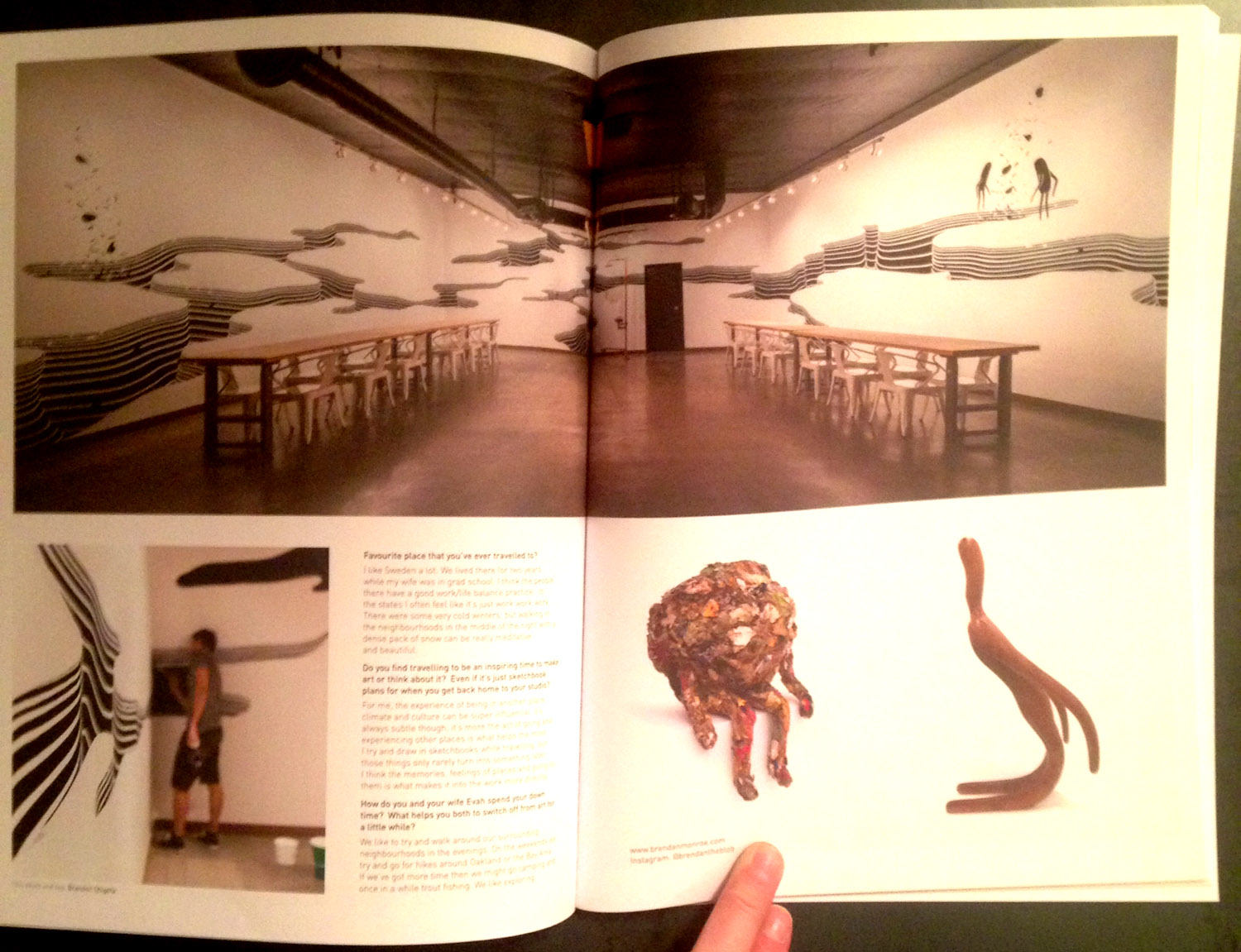

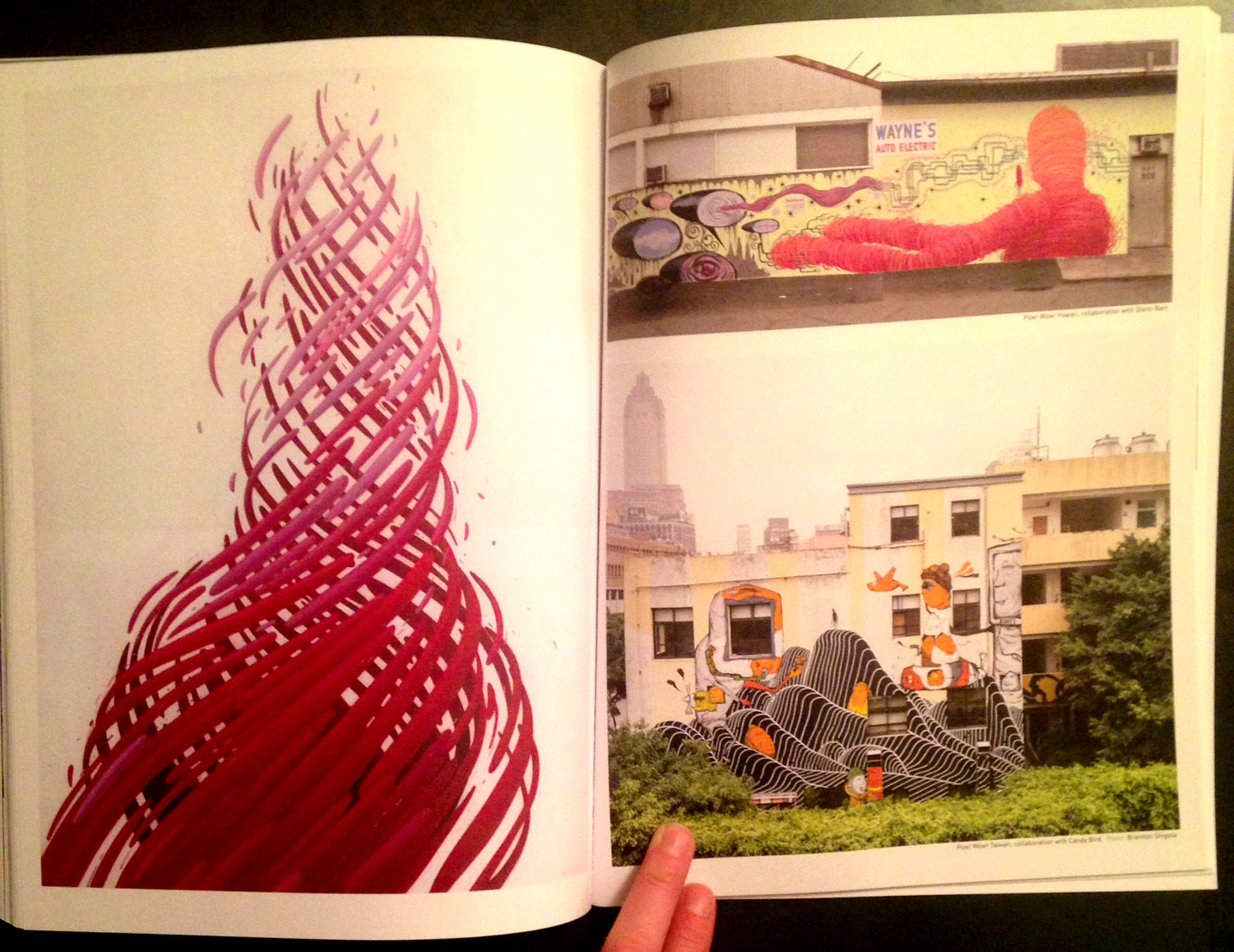

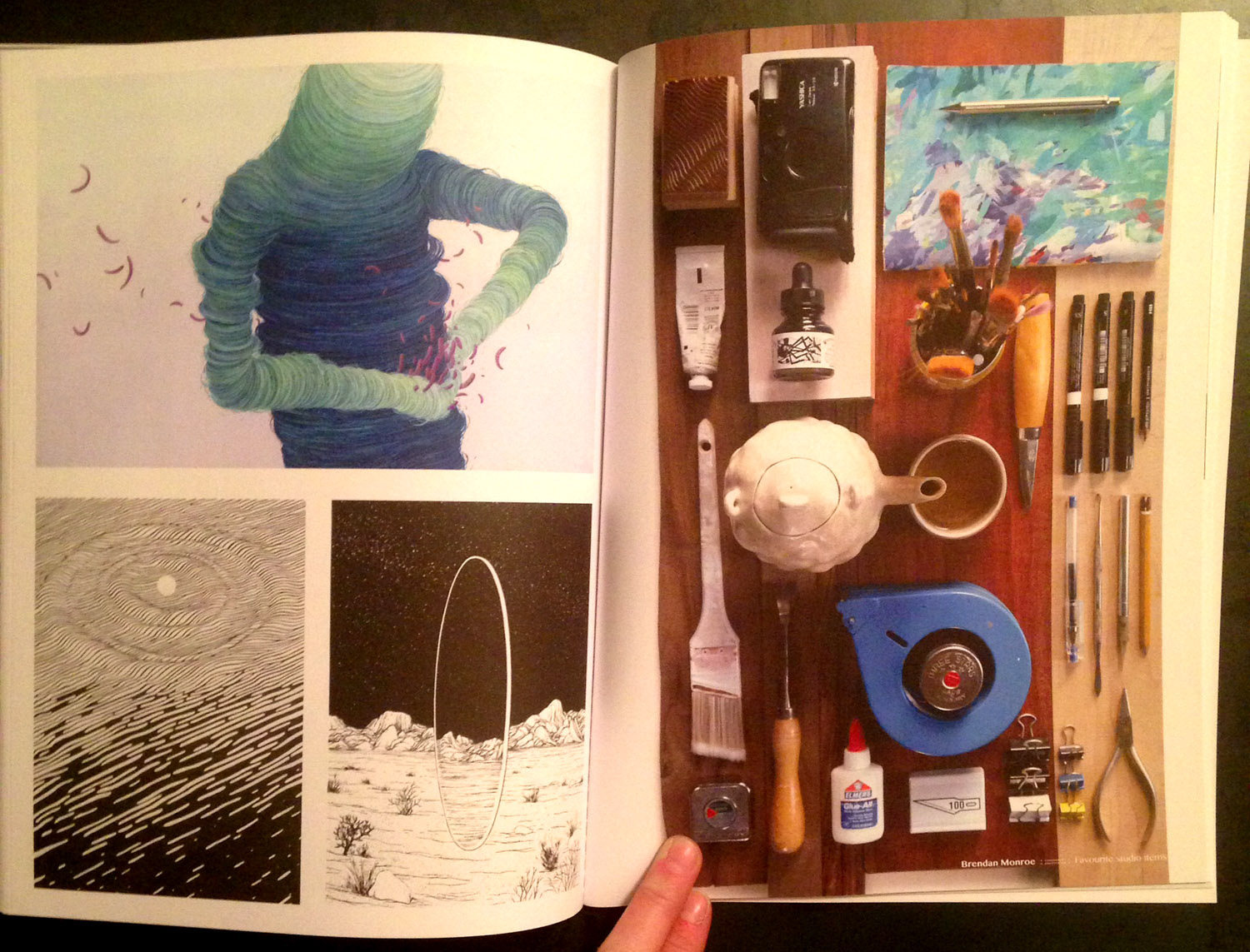

Brendan Monroe featured in Kingbrown Magazine #10

Article of 10 pages

You can get a copy of this very nicely packaged Australian magazine here :

http://www.kingbrownmag.com/shop/

Article of 10 pages

You can get a copy of this very nicely packaged Australian magazine here :

http://www.kingbrownmag.com/shop/

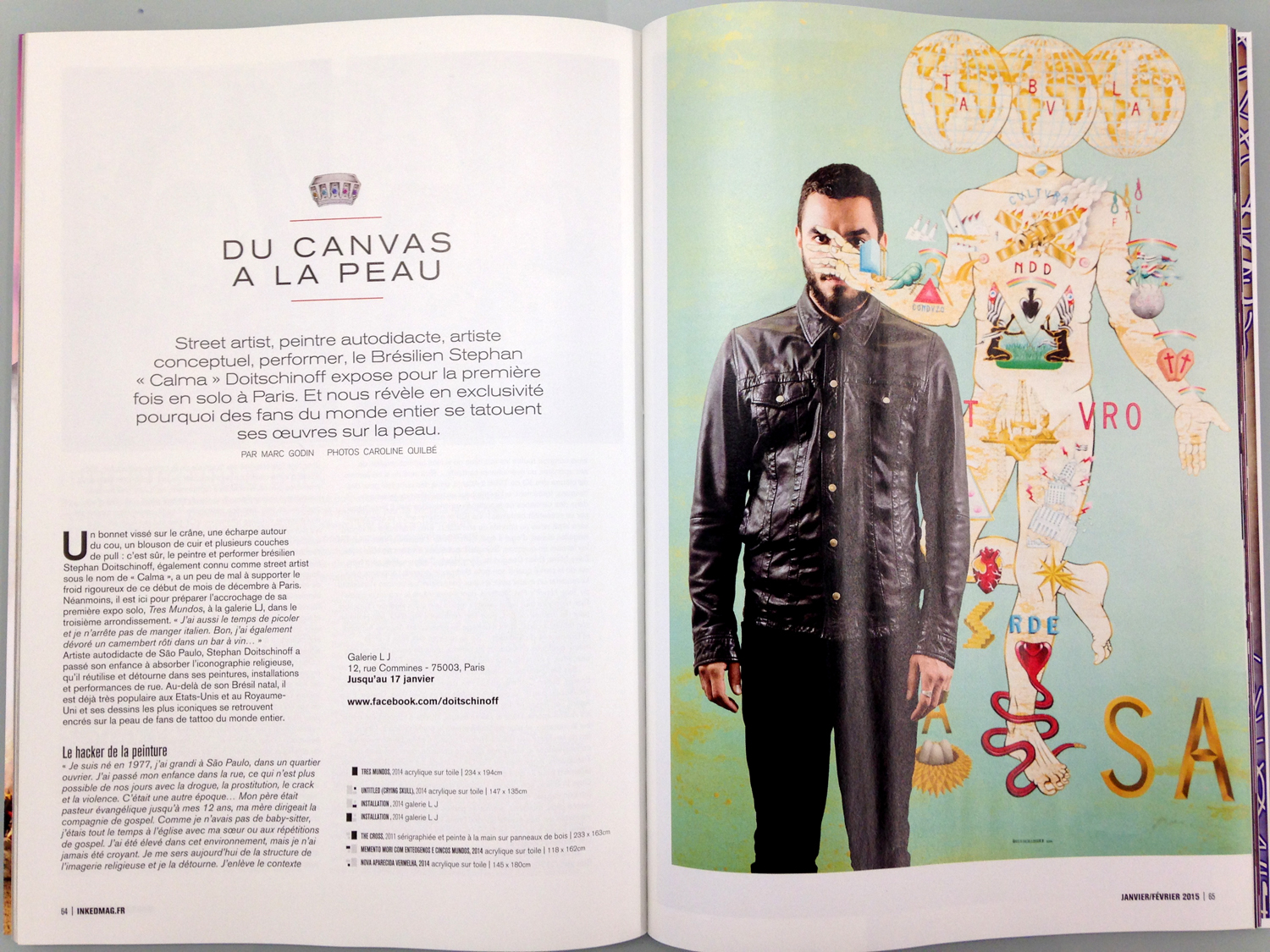

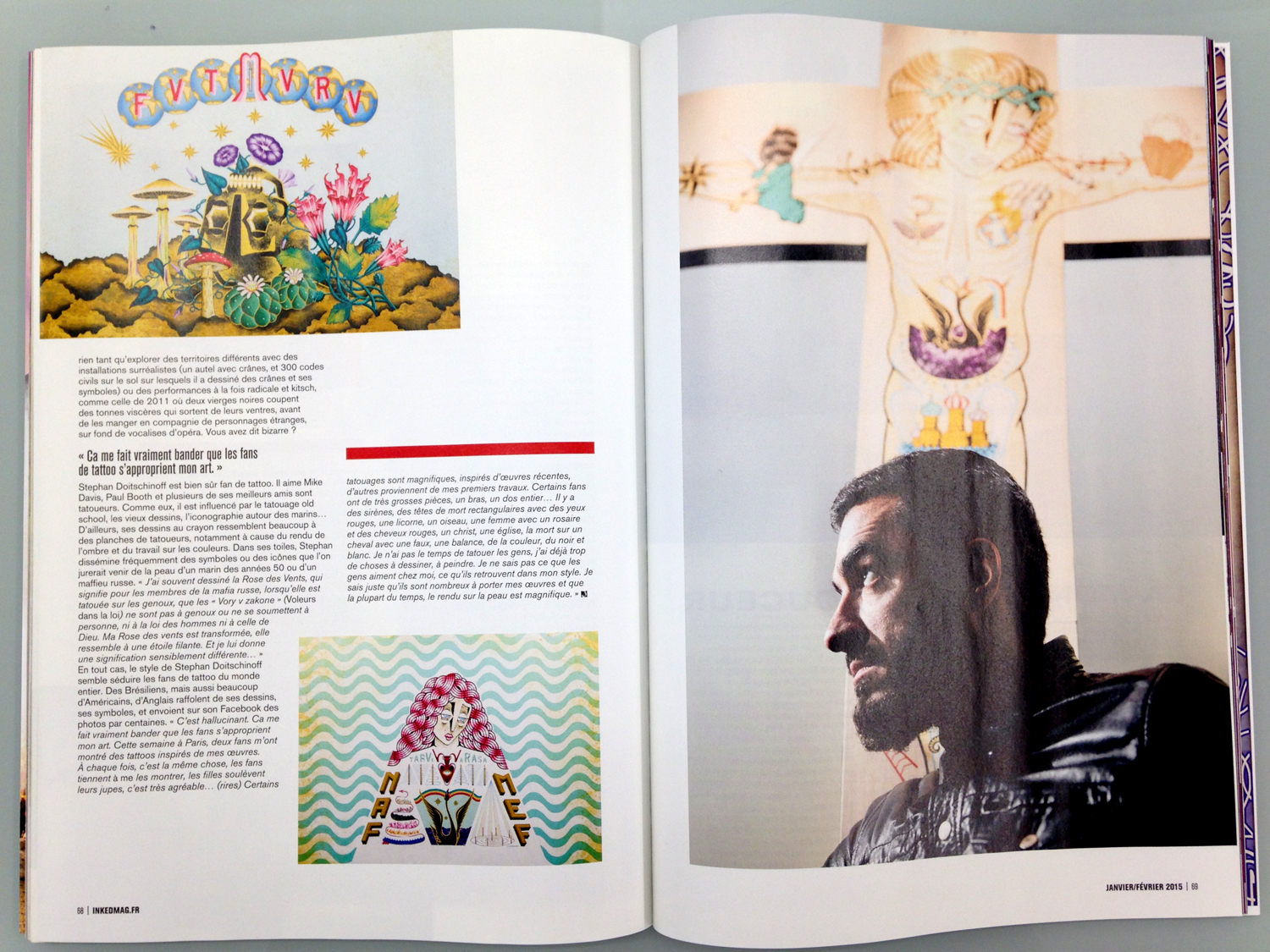

Article of 6 pages + cover art

Read it online here : http://blisssmag.com/march15.html

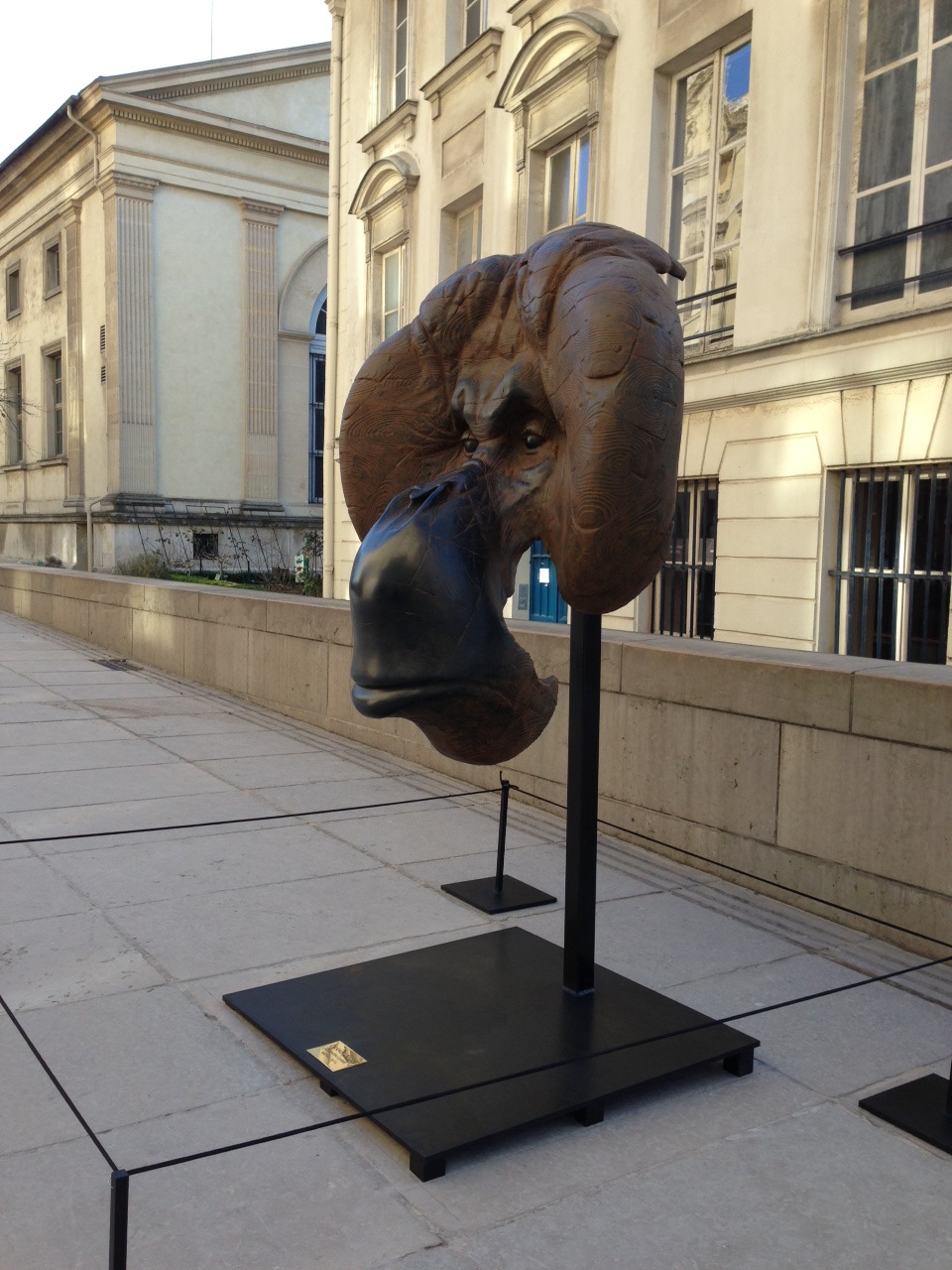

Le Gorille et l’Orang Outang monumentaux de Quentin Garel accueillent les visiteurs du Museum d’Histoire Naturelle de Paris pour les six prochains mois à l’occasion de l’exposition Sur La Piste des Grands Singes.

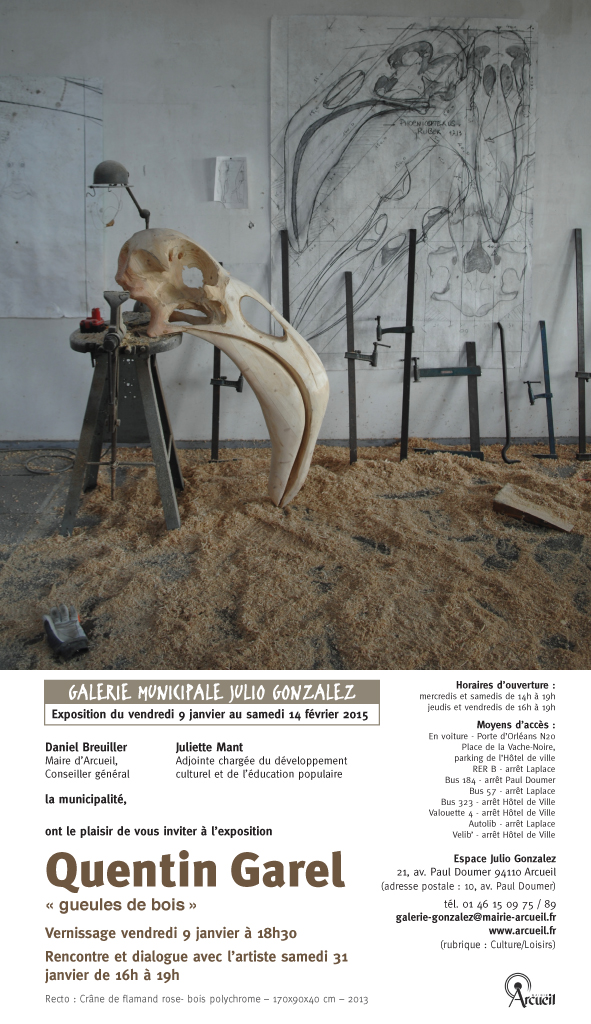

Vernissage vendredi 9 janvier à partir de 18h30, ouvert à tous, en présence de l’artiste

For his upcoming solo show “Tres Mundos” at the gallery

AJ Fosik’s studio reminds me of the parts room at an auto supply super store. Sometimes the piece you need already exists on the shelf. Parts from started and stopped sculptures as well as tried ideas that just didn’t work in the hoped way. At some point the puzzle will be solved. There is a piece to be found or made in order to come up with these fantastic beasts. Roaring dust collectors, hissing compressors, drills, saws, fumes: after all, it is a factory.

You have had a busy year that seems to not be slowing down. Here is the tally: First show in Tokyo, art installation for Music Fest North West, commissions, commercial work as well as an upcoming show in Paris and Art Basel in Miami. The pressure is on and the ideas have to keep coming. What’s that process like?

Who knows? The idea process is a mix of inspiration, drudgery, drive, excitement, stress, and mystery. I go from being so sick of my own work that I don’t even want to turn on a saw, to so manic and stoked to make something, that I ignore everything else in my life to my own detriment. The one thing I’ve learned is to just keeping working. Having unstoppable drive trumps inspiration every time.

I doubt we will ever see you doing a guest DJ set at a club, appearing on a reality TV show or any of that other pop culture nonsense that now surrounds the art world. You are married, have an awesome wife and son, and a nice home in a beautiful city almost completely funded by creativity. I would consider you a working class artist. Is that an accurate description?

Well, I don’t have a trust fund and everything I have to my name is a direct result of my successes and failures as an artist; so yeah it’s fair I suppose. Although being from Detroit, that’s a loaded term and I would hesitate to diminish the struggles of real working class people. I certainly don’t have a time clock to punch or an asshole boss, and I don’t have to worry about my job being sent to china. But yeah, I’m a 9-5er.

You had your first show in Tokyo this year with my gallery. It was a bit of an experimental show with me asking Japanese artists to collaborate on your work. What was your impression for a first timer? Did you notice differences in the way art shows are run in Tokyo as compared to the states? Do you want to go back?

I’m still trying to figure out what the fuck was going on there. I love Tokyo and Japan and I’m pretty sure that even if I dedicated a lifetime to exploring that culture, I wouldn’t even scratch the surface. I found it really interesting how artists and art making are generally held in very high esteem but people don’t really consume art the same way they do here, nobody gives a shit if you make paintings. Artist over there seem to have some sort of cred from either doing corporate work or manga or something else outside the realm of gallery walls before anybody pays attention to what they do. I don’t know if that’s pragmatism or crass commercialism but it’s definitely interesting.

You are part of a group show coming up in Paris at Galerie LJ. You don’t seem to do a lot of group shows. What makes this show different?

I’m thinking about heading back to Paris for a solo show in the near future so I thought I’d test the waters, make sure the Parisians and I still see eye to eye.

In December you are headed to the Art Basel Miami circus as part of theLibrary Street Collective, pop-up group show at the Wynwood Walls. You mentioned you were going for something new with this work. What are you thinking for this piece? How important is it to you at this point to grow and change as an artist?

Change is difficult at this stage of the game but I think it’s essential. There’s a lot of pressure once you reach a certain level of recognition to keep producing whatever it is that grabbed people’s attention in the first place, but that’s a dangerous trap. There’s expectations from people who follow what I do, and that’s something I’m conscious of and want to be respectful to, and then there’s also a huge economic incentive to keep producing the same kind of work over and over. At the end of the day though, if I can’t find ways to keep making things that I find interesting, then I’m full of shit and it’s dishonest and I think the work suffers. I’m always on a search for new angles and inspiration.

I was going to ask a question about your graffiti background and what you think of the trend in galleries to scoop up “street artists” for their galleries, but that’s just beating a dead horse, so never mind. Instead, I am interested in how and if you compartmentalize the method for making pieces for sale in a gallery verses installation verses commercial work? Are you open to direction while doing commercial jobs?

Haha, thanks for not making me talk about street art. As far as all the other stuff, I don’t even think there’s a difference anymore, I used to think of those things as separate, but now I just lean towards making what I make and if people are interested in showing it, or buying it, or posing for an Instagram photo with it, then so be it. I never thought I’d make it this far – and I’m talking about life – let alone making a living as an artist, so really, it’s all cake from here.

Email hello@galerielj.com

Tel +33 (0) 1 72 38 44 47

Adresse

32 bd du Général Jean Simon

75013 Paris, France

M(14) BNF

RER (C) BNF

T(3a) Avenue de France

Horaires d'ouverture

Du mardi au samedi

De 11h à 18h30