Notre exposition Xenolith dans le Télérama Sortir cette semaine (7 septembre 2018)

[SOLD OUT]

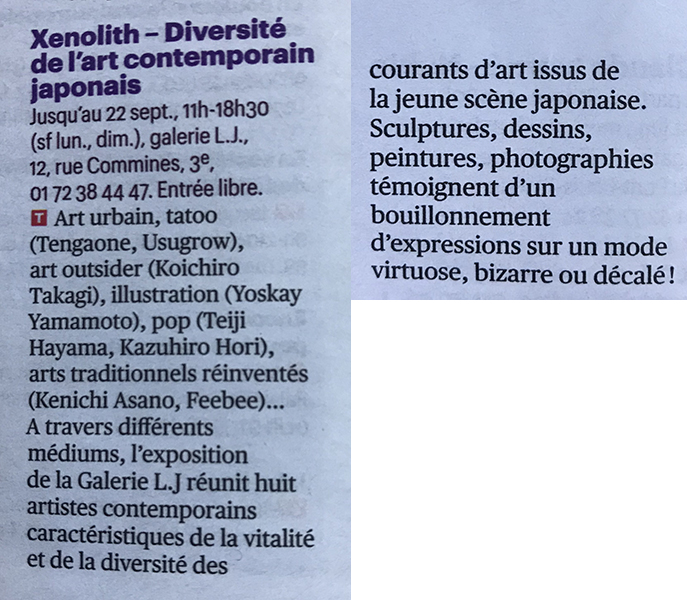

Mu Pan’s very first print on paper, from his original “Tiger” painting, will be available today from 11am (NYC time) on Static Medium. Only 27 copies for only 200$… catch it if you can!

Giclée print on Moenkopi Unryu 55gsm Washi Rag with hand-torn deckled edges.

Literally translated as “cloud dragon paper”, Moenkopi Washi Unryu paper is made in Tokushima, Japan in using traditional Japanese Washi techniques. It is produced by adding long hemp fibers to a wet layer of Kozo (mulberry) fiber on a mold.

37,4 x 95,8cm | 14.75″ x 37.75″

Signed & numbered edition of 27

Available from : https://www.staticmedium.com/product/MuPan/Tiger

Dawn-Michelle BaudeThu, Jun 21, 2018

IN PROCESS: EVERY MOVEMENT COUNTS

Through September 15; Monday–Friday, 9 a.m.–5 p.m.; Saturday, noon-5 p.m.; free.

Marjorie Barrick Museum of Art, 702-895-3381.

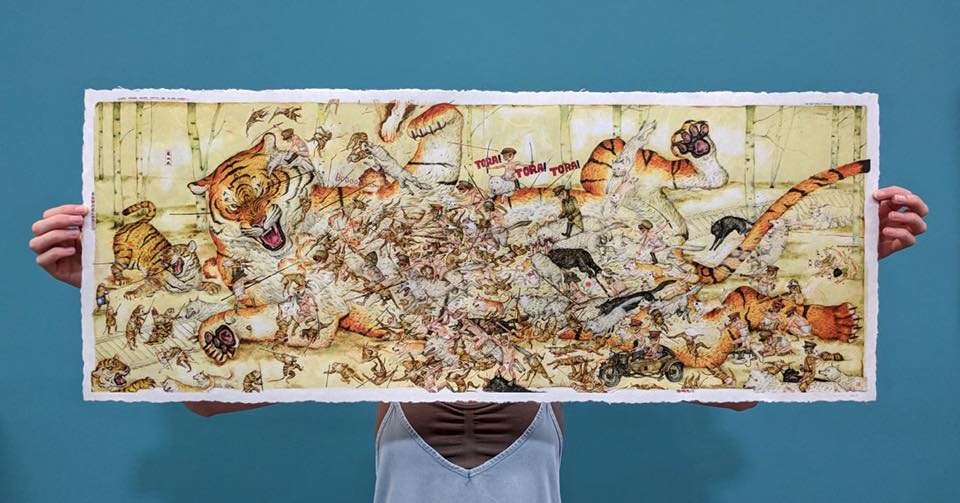

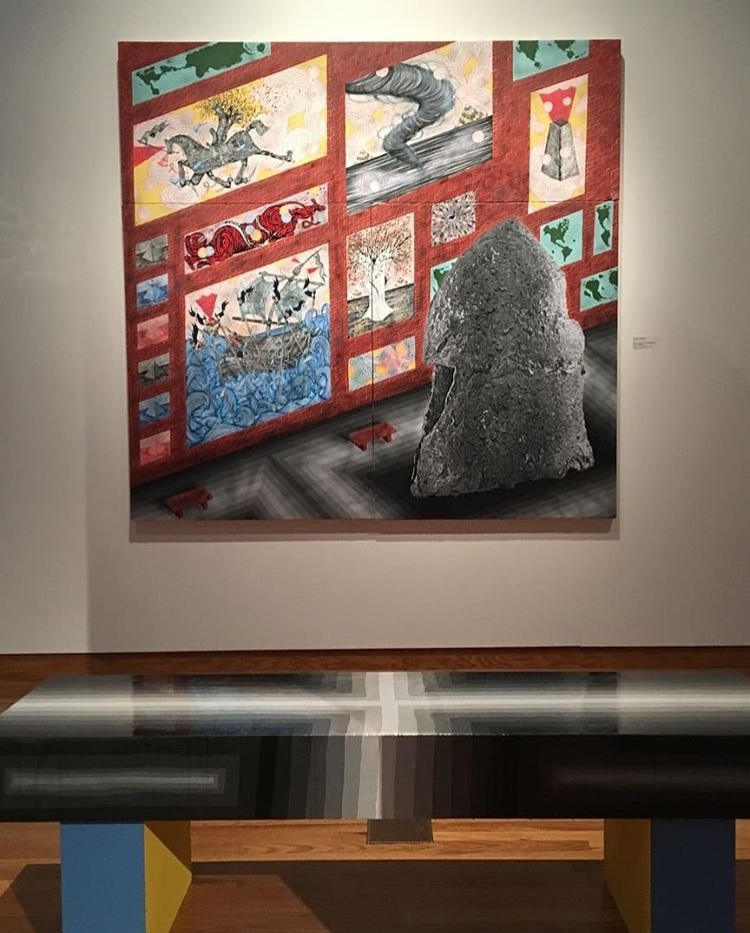

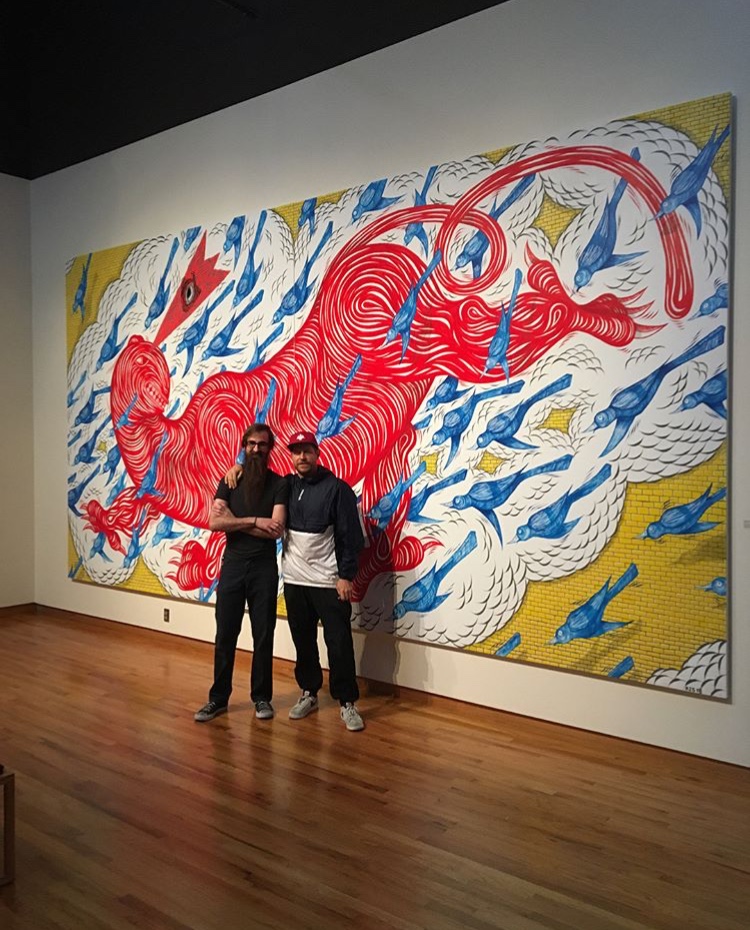

Andrew Schoultz’s In Process: Every Movement Counts boasts so much chromatic swag, the political messaging goes covert. Who could blame the casual viewer for thinking In Process is about how graffiti and street art meet skating culture in a retinal cataclysm? Casual viewer, you are right! Schoultz skids right out of the California skater scene, comic books stuffed in the backpack of youth along with guerilla muralist gear. His tricks are just getting started.

Curated by Andres Guerrero of Guerrero Gallery in San Francisco, In Process thoroughly claims the territory of the Barrick with eight vibrant installations, one 62 feet in length, another 14 feet tall. Painted free-hand, directly on the wall without sketches or—gasp!—digital projection, these installations feature graphic patterns inflected from Schoultz’s learned, symbolic language. His clouds, for example, are contrails that are thrash marks, smoke waves and stylized skies from Persian miniatures (Khwāju Kermānī’s Mathnawi is a favorite source). His bricks ping both animé and the brick-wall motif of mainline Surrealists (especially Magritte and Dalí), but they also harken back to the Lion Gates of Mycenae and Ishtar. The ancient world lurks in Schoultz’s art, sometimes directly in Hellenic vessels, sometime stealthily in, say, his iconic “beast,” a stylized lion sparked from a medieval Alhambra fountain in Spain.

The installations depend on confident, single-stroke, uncorrected lines. In “Spinning Eyes,” those lines deploy large-scale optical interference patterns that literally make our casual viewer dizzy! Centered in each pattern is the all-seeing eye, inspired by the orb atop the pyramid of the almighty dollar and looking in the direction of 24-hour surveillance. Or consider the “Untitled” wall, its contrast lines demarking 32 divisions of hue in a kind of tonal accordion. Primary colors confront each other in the middle, while secondary colors gradate toward the edges, recalling the color field paintings of Louis Morris. Affixed to the panels are four high-relief vessels, their cinnabar-red edges generating a fetching afterglow, their contrasting forms inscribed with classic labyrinthine patterns or broken into bits like archeological finds.

Ruins, remnants and rubble figure in several of Schoultz’s works, including the thematically complex “Infinity Plaza,” with its comic dystopian public-park meltdown, or “Eyes (Currency),” one of the small-format gems, with 5K of shredded dollars collaged as background material. Money and maps, flags and war gear hint at the show’s big ideas about the territorial shape of civilization. Another untitled installation displays six medieval European war helmets that appear photorealistic at a distance but dissolve into camouflage blobs up close.

All in all, the theatrical, happy vibe of In Process wows the casual viewer, while the more contemplative among us ponder the show’s deft political protest. A robust exhibition not to missed.

Andrew Schoultz inaugure ce samedi 2 juin sa plus large exposition personnelle muséale à ce jour, au University of Nevada Barrick Museum of Art, à Las Vegas.

“In Process: Every Movement Counts”, comprend 8 installations réalisées in-situ ainsi que 25 oeuvres.

A voir jusqu’au 15 septembre 2018.

+ infos

May 24, 2018 — A sculpted cascade of colorful dominoes is the latest installation to greet visitors to Downtown’s Triangle Square as part of the art initiative ROAM Santa Monica.

Installed this month, “Tipping Point” by Los Angeles-based artist Andrew Schoultz creates an optical domino effect with a linear series of six toppling rainbow-colored blocks that stand 10 feet tall.

The sculpture composed of “repeating monochromatic patterned pillars” is the latest installment for DTSM, Inc. and the City of Santa Monica Art Commission’s public art initiative “to activate the public realm and expand cultural offerings” Downtown, officials said.

|

| “Tipping Point” by Andrew Schoultz (Images courtesy Downtown Santa Monica, Inc.) |

“Onlookers are invited to experience Schoultz’s sculpture from different angles and muse on the struggles that lie between visual clarity and complex truth,” Downtown officials said.

“Tipping Point will cascade indefinitely at Triangle Square.”

Known for his “vibrant visual systems style,” Schoultz’s art is featured at institutions worldwide, including the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the Los Angeles Contemporary Art Museum, Downtown officials said.

He has painted public murals on walls in Manila, Philippines and Jogjakarta, Indonesia, as well as on skate parks, an airplane and a Tesla.

“Tipping Point” is his first major public art sculpture.

|

ROAM was launched after Downtown officials approached the City with the idea of a rotating public art series that would help “create environments that foster positive social interactions and enliven public spaces,” Downtown officials said.

Artists featured in this series, include FAILE, Jen Stark, Ben Zamora, Brenda Monroe, Danielle Garza, Jeanine Centuori & Russell Rock, Kate Johnson, Kristen Ramirez, Nataša Stearns, Nate Frizzell and Sean Yoro.

Triangle Square is located on the Colorado Esplanade and Third Street, adjacent to the Sears building and Santa Monica Place.

For more information, visit ROAM SantaMonica.com.

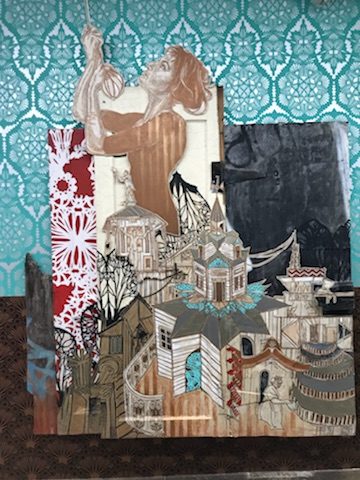

Swoon and Andrew Schoultz are currently presenting site specific installations in BEYOND THE STREETS, Roger Gastman’s massive exhibition of street art from May 6th to July 6th 2018 in Los Angeles. BEYOND THE STREETS focuses on artists with a documented history of mark making and rule breaking as well as a current, robust studio practice primarily derived from the graffiti and street art movements. BEYOND THE STREETS is not intended to be an historical retrospective but rather an examination of cultural outlaws who embody the spirit of the graffiti and street art culture. The exhibition includes well known artists whose work is influenced or inspired by these risk takers and whose efforts have elevated the movement to new heights.

+ infos

Badass Woman spotlights women who not only have a voice but defy the irrelevant preconceptions of gender.

Swoon’s ethereal paper sculptures have hung in New York’s MoMA and Los Angeles’s MoCA, but you’re just as likely to find her work on a brick wall in a forgotten street.

The artist, born Caledonia Curry, is a study in contrasts. A classically trained painter-turned-street art heavyweight, she’s best known for her breathtaking, goddess-like cut-out portraits, which have found fans in the fine art and graffiti worlds alike. Wheat pasted in cities across the world, they’re raw but also dreamy and—unlike most street art—boldly feminine.

“At first I really fought it. And then I was like, ‘You know what? Fuck this!’” Swoon says of her soft aesthetic. “Femininity and delicacy, all of these qualities are not respected on a grand scale. We don’t really have a cultural history of [appreciating] female genius, let’s call it, people who fully embody their art and their work in ways that express their femininity.” So she carved out a genre where girlishness and grit go hand in hand.

Swoon, 40, describes her early childhood in Daytona Beach, Fl., as chaotic. Her parents were both heroin addicts who struggled with mental illness and suicidal tendencies, themes that recur in her work. But her preteen years were characterized by more stability. Her father got clean, and when Swoon was 10, her mother enrolled her in an art class for retirees; somehow, there she found her place. Art became a mode of expression, therapy, and activism for Swoon, who launched an ongoing building and beautification project in Haiti after the 2010 earthquake. Below, she lets us into her colorful world—including her unlikely embrace by the boys’ club and that time she illegally sailed through Venice on a raft made of garbage.

Her first big fail: “Artists will tell you they were artists their whole lives,” says Swoon. But she points to the moment she stepped into that art class as a 10-year-old as her awakening. “The 80-year-old retired painters adopted me; they taught me how to paint. I’ve been a focused, confident artist because of them.” Years later, thought, her first attempt at street art was a disaster, she recalls. “I worked on it for a couple months, and then I went and tried to put it outside and it was a total failure. I must have been 22, and it was a linoleum block carving portrait. I didn’t know what I was doing. It came down immediately,” she says with a laugh. “But I kept going.”

From hideout to breakout: Swoon’s second attempt was more successful. By the early aughts—shortly after she graduated from Brooklyn’s prestigious Pratt Institute—her wheat-pasted murals had gained widespread recognition, though she kept her identity hidden behind the moniker Swoon. She was working as a waitress and selling art out of her apartment, when a friend in the art community told her that Jeffrey Deitch—the experimental curator whose gallery served as a launchpad for the most exciting, young talent—had been asking around, trying to connect with the mysterious Swoon. In 2005, they unveiled their collaboration: Swoon filled Deitch’s gallery with a sprawling dreamscape of paper sculptures that rocked the art world.

“Strangely, the Museum of Modern Art contacted me before Jeffrey did,” she says of her sudden popularity. But Swoon didn’t quite understand, or at least believe, that they were interested in her work. “I was like, ‘Why are you contacting me?’ They were like, ‘Can you bring some art by?’ And, I was like, ‘…For what?'”

Not one of the boys: Swoon is one of the only, and arguably the most prominent, women to achieve her level of success within the street art genre. But the boys’ club was surprisingly welcoming. “I think people expect that you’re going to get a lot of sexism, but for the most part everyone just wanted to make shit, and they were excited, and everyone just supported everyone else. I honestly think that there’s a lot more sexism higher up in the art world than there was when I started out making [art] on the street,” she says, adding, “It is a little weird that now I make such feminine work a lot of the time because I was a total tomboy. My proudest accomplishment is being an artist that young women can look at and say, ‘I can do that.'”

Battling mental illness: Swoon’s biggest obstacle has been “my own mind,” she says. Watching her parents struggle with addiction and mental illness, at one point she thought her life would inevitably take a similar path. “When you have trauma at a young age, which I did because my family was so unstable, it starts to come out later in life. So in my 30s I started losing it. I couldn’t live with myself, so I had to do all this deep work. I had to start going to therapy, I was reading, writing, journaling, researching trauma to try to be a person that feels grounded.”

Eventually, she was able to make peace with her turbulent childhood, even letting go of long-held resentments. “That has been a long process and has been a lot of uncovering.” A large part of that, for Swoon, was channeling her complex emotions into her work. “It’s really about the discovering [what you’re feeling] in the first place. Once you discover it, turning it into art—that’s how I live; that’s who I am.”

Pranking the Venice Biennale: Swoon has shown her work in various settings, from Miami’s Wynwood Walls to her total takeover of the Cincinnati Contemporary Arts Center. But her most outlandish project yet was part performance art, part social experiment, and part fun-loving, dumpster-diving stunt. Along with a band of anarchist artists, she designed a fleet of ships constructed entirely of New York City trash (think steampunk Captain Hook). The merry travelers began their journey on the coast of Slovenia and crashed the 2009 Venice Biennale, inviting onlookers lining the canals to hop onboard and party with them. Customs was, to say the least, confused.

Art as activism: Swoon believes that “spaces of wonder” can transform communities in crisis, which is the mission of her organization, the Heliotrope Foundation. After the devastating earthquake that hit Haiti in 2010, she started a sustainable building project in two local communities to provide much-needed housing and bring color back into the leveled towns, which would become the first initiative under Heliotrope. She’s also now working to restore an abandoned church in Braddock, Penn., repurposing it as an artist-run ceramics workshop and community center.

Looking ahead: With her wheat-paste murals, lace-like sculptures, garbage boats, and performance art, Swoon is a true multimedia artist. Up next: “Some time working in experimental film.”

Andrew Schoultz painted the now-reopened Community Skatepark in Las Vegas with The UNLV Marjorie Barrick Museum of Art and the Clark County Winchester Cultural Center. Schoultz is known for his deep connection to skateboarding, painting numerous skateparks, collaborating with skate brands, and recently painting the Skatepark of Tampa for their 2017 Tampa Am.

“This Marvelous and Turbulent World: New work and installation by Andrew Schoultz”

commissaire : Josef Zimmerman

24/04 > 27/05/18

Andrew Schoultz inaugure une nouvelle exposition personnelle muséale au Fort Wayne Museum of Art, à Fort Wayne dans l’Indiana, ce samedi 24 mars. Il s’agit de la 2e intervention d’Andrew dans ce musée où il avait déjà réalisé une installation monumentale en 2015.

“Le chaos et la destruction sont des thèmes récurrents dans mon travail parce que ce sont des phénomènes constants autour de nous. Qu’il s’agisse des nombreuses guerres en cours de par le monde, les catastrophes naturelles qui semblent maintenant régulières, les catastrophes causées par l’homme sur l’environnement qui deviennent de plus en plus courantes, ou encore la crise économique qui écrase les classes pauvres et moyennes des Etats Unis depuis des années, je constate que l’on ne peut pas parler de l’une sans évoquer toutes les autres, donc cela devient un sujet assez monstrueux dans son ensemble“.

+ infos

WIP and show pictures

http://neocha.com/magazine/the-art-of-war/

The Art of War

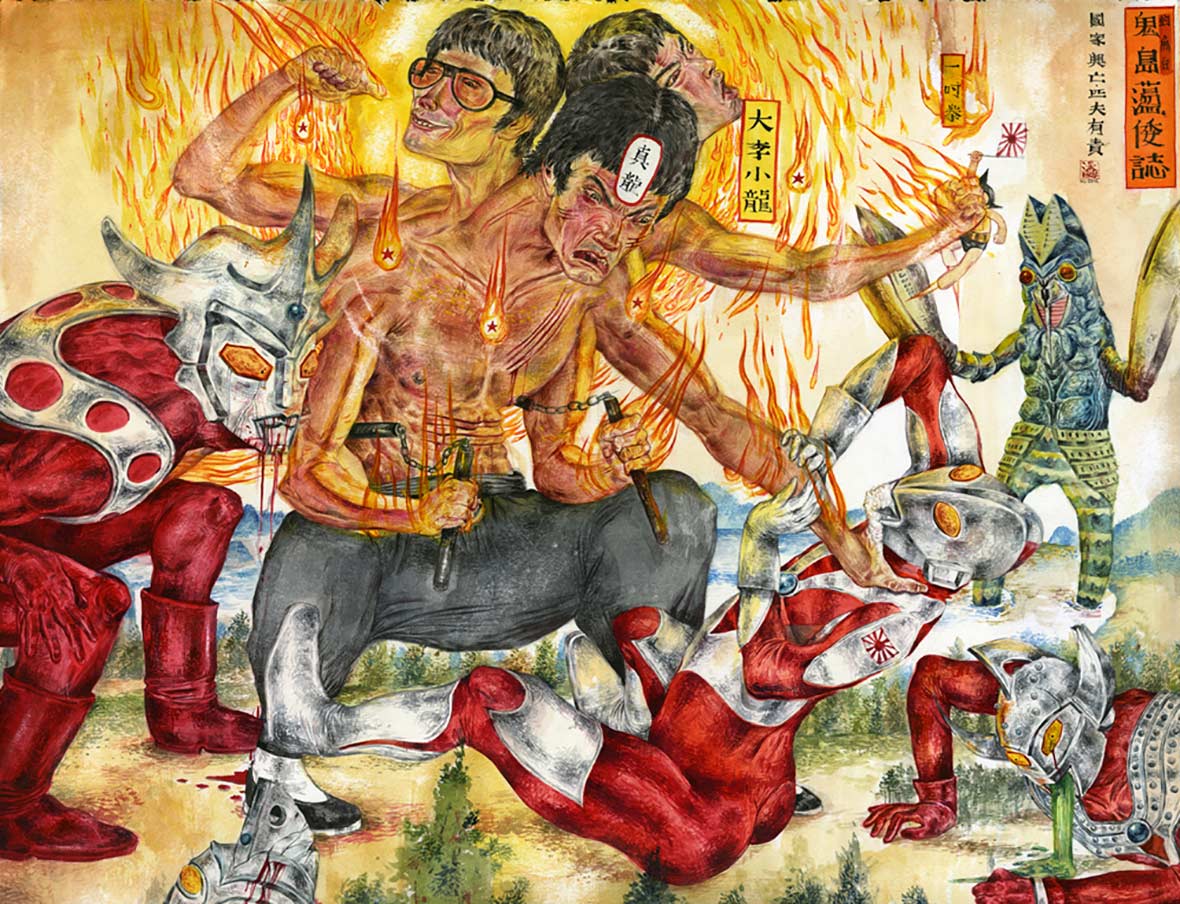

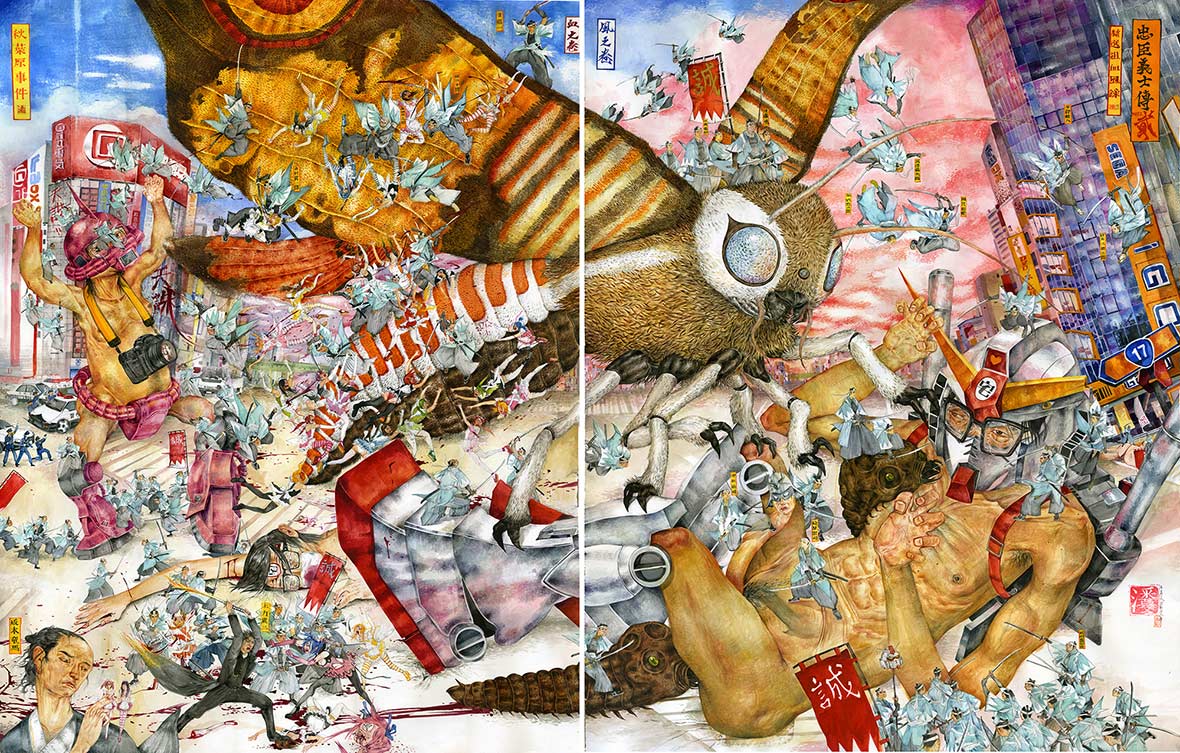

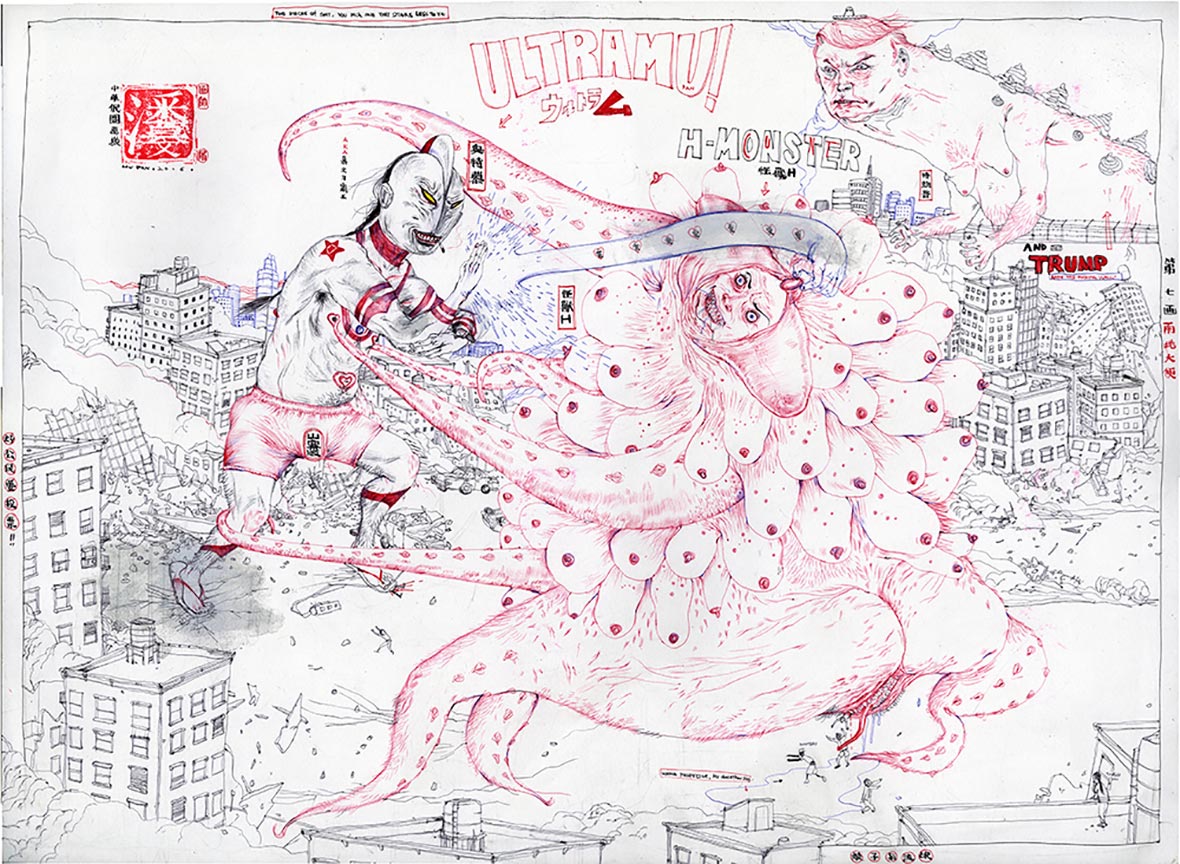

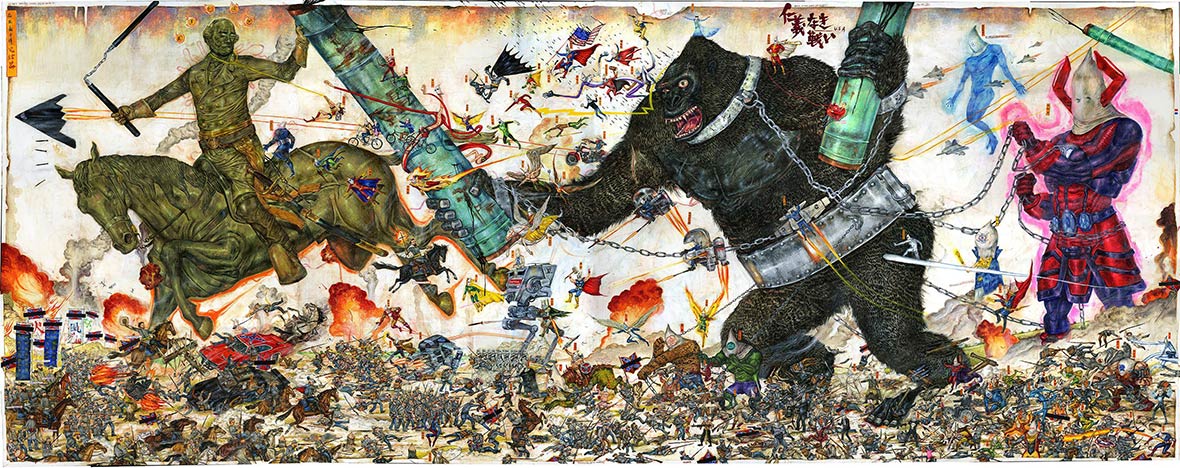

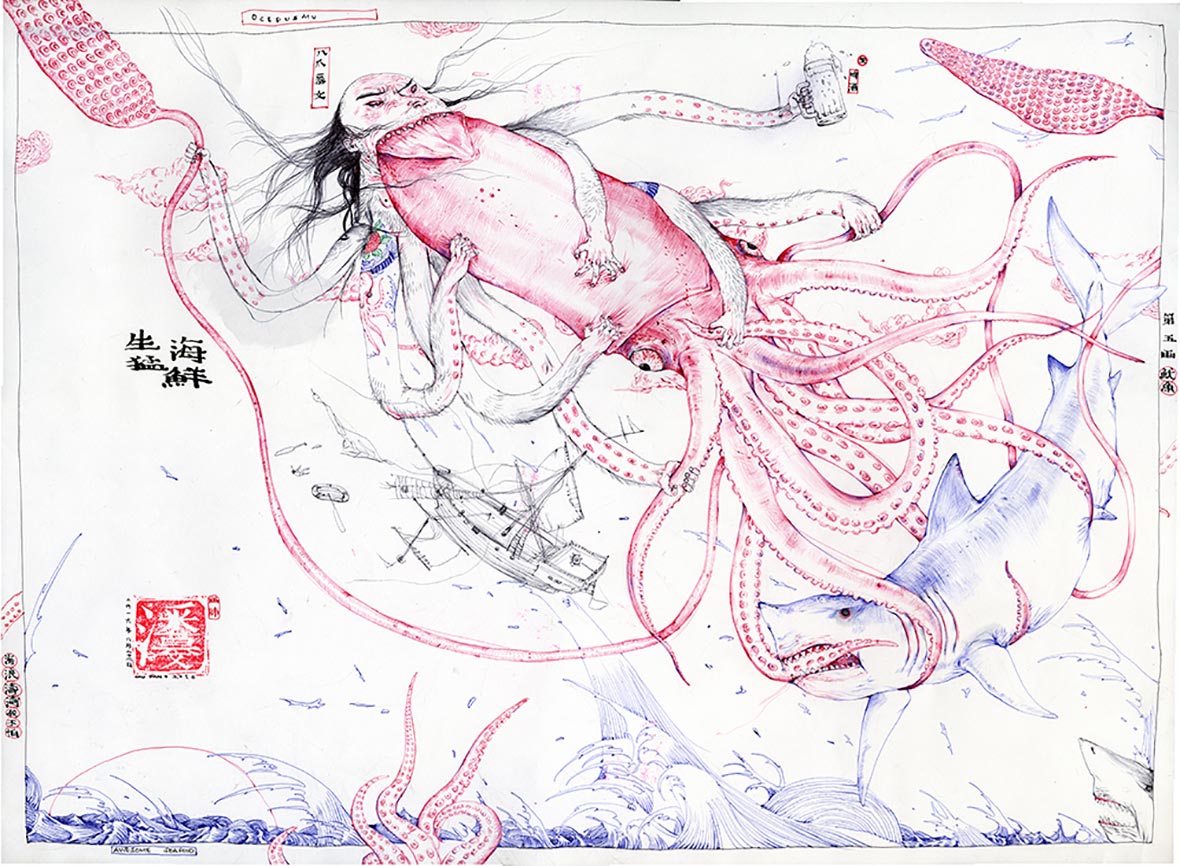

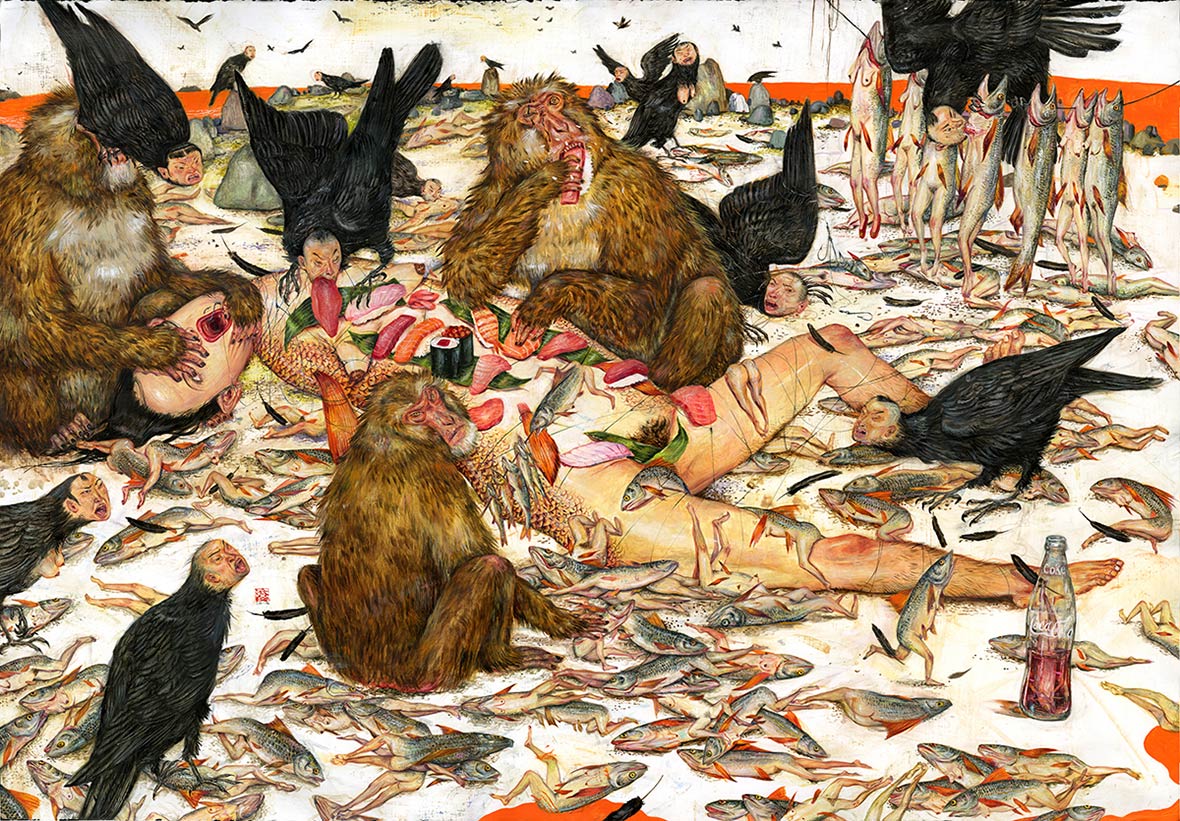

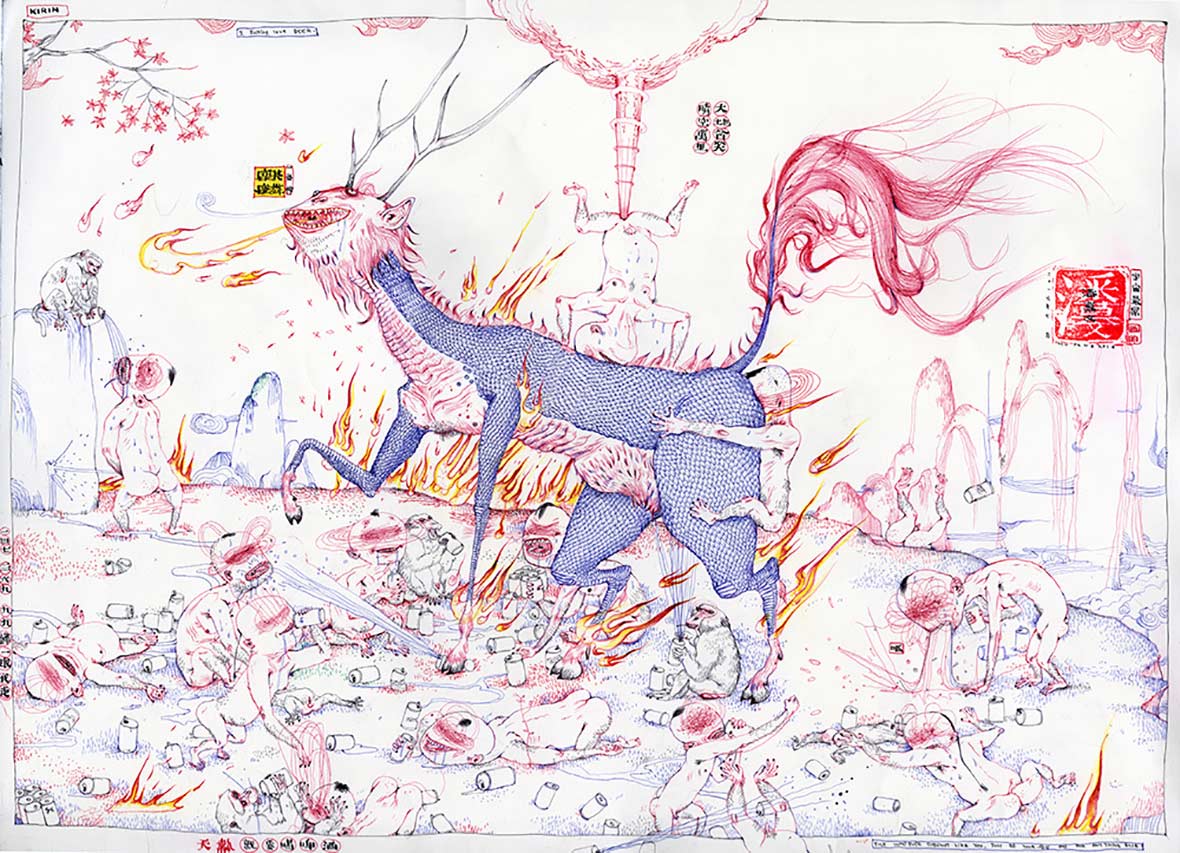

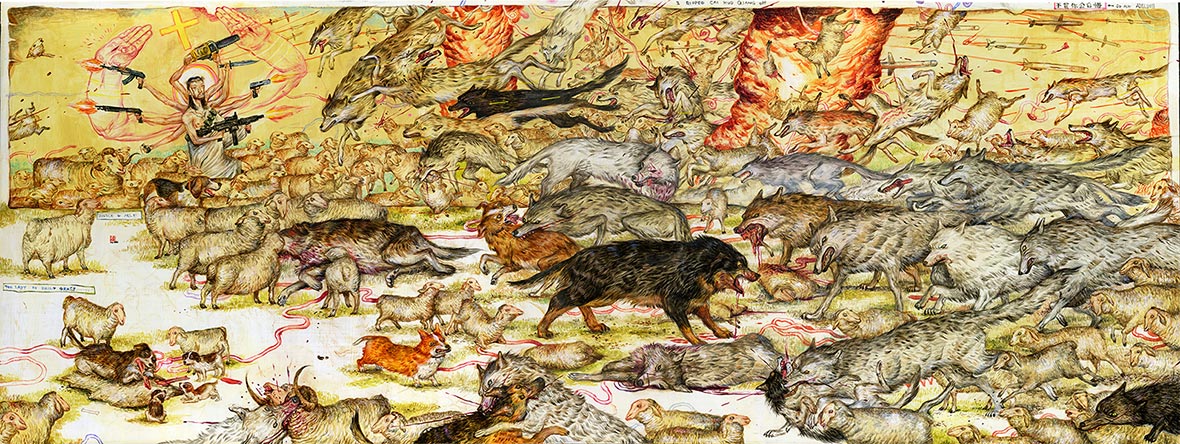

Mu Pan is a Taiwanese artist currently based in New York City. With influences ranging from Hong Kong cinema of the 1980s and 1990s to Japanese manga and kaiju movies, Mu incorporates elements of Chinese history and mythology to tell epic stories and legends with modern sensibilities. Mu’s artwork is never about art for its own sake – in his own words, “I am just an otaku who draws.”

潘慕文(Mu Pan)是一名现居纽约的台湾艺术家。他融合中国历史和神话元素,用画作来讲述具有现代感的史诗故事和传奇,从80、90年代的香港电影到日本漫画和怪兽电影,都对潘慕文的作品产生了很大的影响。他的艺术作品从来不只是为了创作而创作,用他自己的话说,“我只是一个画画的宅男”。

As an artist who tells stories of epic, large-scale battles, war is one of Mu’s primary inspirations. He shares, “War, to some degree, is a beautiful thing to me. War creates great characters, and it also writes history. You’ve got to be a great artist in order to fight a war as a commander. There are so many arts you have to master in warfare, such as the formation, the economic concern, the time, the strategy, the geographic advantage, the numbers difference between you and your enemy, the art of brainwashing for loyalty, and the sense of mission. It costs a great amount of patience, and it also requires a high level of charisma and intelligence. Whether it is for invading or defending, to me it is just beautiful to see how a person can unite people’s individual strengths to become one great power to fight against the opponent.”

作为一个描绘史诗、大规模军事场面的艺术家,战争是他创作的主要灵感之一。他解释道:“对我而言,战争某种层面上是一件美丽的事情。战争创造了伟大的人物,也书写了历史。要成为战争中的指挥官,首先你必须是一位出色的艺术家。在战争中,必须掌握的艺术非常多,编队、经济问题、时间、策略、地理优势、我军与敌军在人数上的差异、关于忠诚与使命感的洗脑式说话艺术等等。这些都需要很大的耐心,同时也需要极大的魅力和智慧。无论是侵略还是防守,对我来说,看着一个人如何团结其他个体,凝聚成为对抗对手的巨大力量,这个过程真是充满了美感。”

Mu often draws from the theatre of modern events to find inspiration for his work. “Usually, when I’m excited about something I saw or read on the media, or from my daily life, I first associate the subject with a monster or some creatures on a large scale, then think about who it will be fighting with.”

潘慕文经常从现代事件中汲取创作的灵感。 “如果我从媒体、日常生活中看到或读到一些令我感兴趣的东西时,我会把这个主题延伸联想出某个怪物或是一些体型庞大的生物,然后去构想这只怪物开战的对象。”

With regards to his creative process, Mu is about spontaneity and creating in the moment. He never creates preliminary sketches for a painting, preferring to work freely and make changes on the fly. As each painting progresses, it reflects the emotions and events of his daily life. “I let the piece flow with whatever is happening in my life,” he explains. “This gives me the motivation to keep going day after day.”

谈到自己的创作过程,潘慕文说主要都是自发性和即兴的创作。绘画时,他从来不会先画草图,而是更喜欢自由地创作,随心所欲地作出改变。每幅画在完成的过程中,反映出的正是他平日生活里的情绪和经历。他解释说:“我把作品与我生活中发生的一切交织在一起,这给了我继续前进的动力。”

For Mu, art is a way to channel man’s energy, destructive power, and warlike disposition within the constraints of modern society. “I worship the strength of men and animals,” he tells us. “I dream to have the dominating power to rule, to destroy, and instill fear into my enemies. Of course, it’s impossible. No one can have this kind of power in today’s world. So I created my own world for myself with my images. In my images, I can be whatever I want to be and eat whoever I hate. Every monster I draw is actually a self-portrait.”

对潘慕文来说,艺术是在现代社会的制约下,人们得以发泄内心能量、破坏力和战争倾向的一种方式。他解释道:“我崇拜人和动物的力量。我梦想拥有支配权力来统治、摧毁,让敌人畏惧我。当然,这都是不可能实现的。今天的世界上没有人能拥有这样的力量。所以我用画像来为自己创造这样一个世界。在我的画里,我可以做任何我想做的事情,吃掉我讨厌的人。我画的每个怪物其实都是一幅自画像。”

Email hello@galerielj.com

Tel +33 (0) 1 72 38 44 47

Adresse

32 bd du Général Jean Simon

75013 Paris, France

M(14) BNF

RER (C) BNF

T(3a) Avenue de France

Horaires d'ouverture

Du mardi au samedi

De 11h à 18h30