4 April 2015

AN INTERVIEW WITH ALLYSON MELLBERG TAYLOR

I’ve never had the pleasure of meeting

Allyson Mellberg Taylor in person, nor do I know the sound of her voice. We only occasionally share (heart felt) letters a couple of times a year. Despite this seeming ‘unknowing’ of one another, I have always felt a personal connection to both her work; its grotesque beauty, its Sci-Fi heart, as well as to the lady herself. A

painting she made for the ‘Spirit Board’ show I curated back in 2011 remains one of my most treasured pieces in my home.

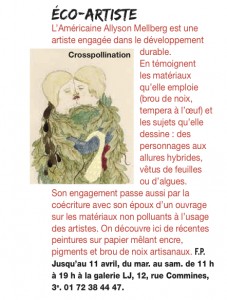

Her newest body of delightfully strange paintings, ‘The Planet of Doubt’, opened last month at Galerie LJ in Paris, a large exhibition of over 40 new pieces that she managed to conjure into being despite her responsibilities as a wife, mother and teacher. This prolific nature is a huge inspiration to me, and her work, while retaining many of the similar themes and aesthetics of previous exhibitions, continues to grow in simple elegance and strength. I recently had the honor of asking Allyson some questions, & upon reading her responses feel even more of a kinship with this special lady.

Do you imagine your figures living within the same narrative ? The same world?

I think the answer is yes. If not the same world, definitely the same solar system. But it’s a big space so there is a lot of room for individuals to wander and explore. Or maybe everyone is an introvert? Every once in a while I have drawings that include many figures so they get together now and again.

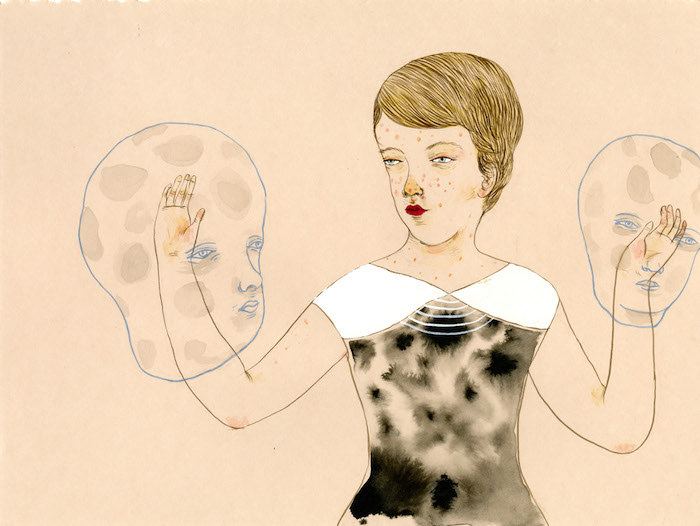

One of the things I am drawn to most about your work is the delicate beauty present, how your figures engage with others and their surroundings in such a gentle way and yet, they are often marked with diseased looking skin. Why make this “ugly” choice ?

I have always been drawn to the grotesque especially when paired with a gentle, delicate quality –I’m thinking specifically of old medical illustrations of skin diseases where the beautifully illustrated figures are marred by psoriasis or pox, etc. They always look so dignified. I like the idea of my figures being passive, gentle observers who are able to integrate with their surroundings to the point of being covered.

Science Fiction, in particular, ‘Dr.Who’, has been a great influence on your work. Even the title of your new exhibition ‘Planet of Doubt’ is culled from a sci-fi short story involving space travel. Can you talk about these inspirations ?

I have been a serious Doctor Who fan since the early 80’s when I watched Tom Baker as the Doctor on PBS with my big brother. Then, thanks to the internet I was able to go back and watch all of the very first b&w 1960’s episodes which I fell in love with too… and I love all of the new series as well… I also enjoy reading science fiction, Ursula K. LeGuin, Arthur C. Clarke, those crazy short story anthologies edited byIsaac Asimov… I love all of that stuff. The main reason it is inspiring/influential to my work is the ability of good science fiction to discuss real social and ecological issues in a way that is just enough outside of our normal existence that we can consider alternatives to our current reality without becoming defensive/unreceptive. Ursula K LeGuin is a great example of a writer who has explored how we deal with gender (Left Hand of Darkness) the environment (The Word for World is Forest), and the consequences of our actions/the actions of humanity (the Lathe of Heaven)… but there are so many more great examples. I also love Haruki Murakami so much but I think that his work is considered to be more surrealism than Sci-Fi.

How important is your sketchbook to your process ?

I really need my sketchbook! It helps me think/plan/write/draw. If you went through my last two sketchbooks you would find mini versions of nearly every drawing in my recent show. And you would also find a lot of weird doodles, writing and lists. Having a sketchbook really helps me think. I also appreciate it more now that I am a Mom because when my daughter naps in the car I get a lot of stuff done in my sketchbook. Actually I think about a dozen of my newer pieces were drawn on good paper in the car, in a parking lot while M was napping. Ha! I am very particular though. My sketchbook paper has to be smooth, off white rather than bright white, and has to be able to handle ink. And it can’t have a decorated cover…. I would say that I am pretty superstitious about sketchbooks and have definitely left ones with bad energy empty on the shelf. I have no way of rationally explaining that, its just a feeling.

Nature plays an important role in your work and I know you care deeply for the garden you share with your husband. You even make your own inks and use antiquated methods such as egg tempera. Can you talk about why this is so important to you?

When I was in undergrad, several of my professors had health issues related to using solvents and that had a big impact on me in terms of non-toxic printmaking. Then I went to graduate school and met Jeremy and he was doing all of this really in-depth research on non-toxic, sustainable, and earthen pigments. It was a revelation to see what he was making and to really consider the effects of some of the materials I was still using. After learning all of this stuff from him, it was sort of like watching cows get slaughtered and then not being able to eat meat anymore… it’s hard to go back once you know. So I purged my studio of anything toxic and found that I didn’t miss any of it. I am so grateful to Jeremy for sharing all of this knowledge with me and really being an inspiration in terms of making beautiful, smart work that is also not harming the earth. Once I started working without any toxic pigments/solvents, I remembered an egg tempera demo from undergrad and decided to give it another try. I found it to be perfect for me it was non-toxic (because of my pigments), dried fast, and had a beautiful clarity of color that I love. Our garden has been a great opportunity to grow pigments right next to our food and process dyes and inks our selves. We just moved so we are building a new garden right now, which is exciting and daunting all at once. Gardening is very important to our whole family, it’s a form of meditation, exercise, it’s something we do together, our home really won’t feel like home until that is up and running.

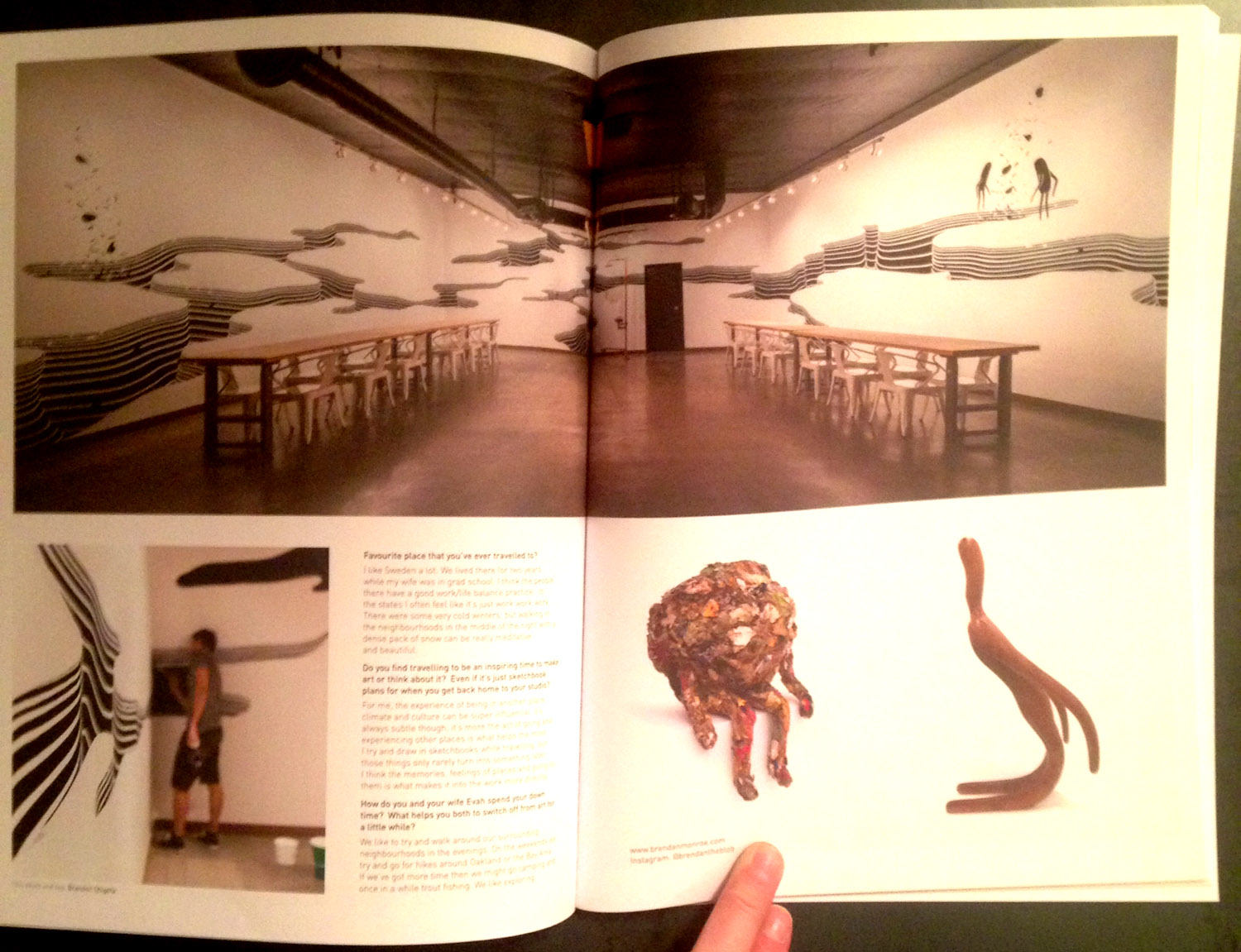

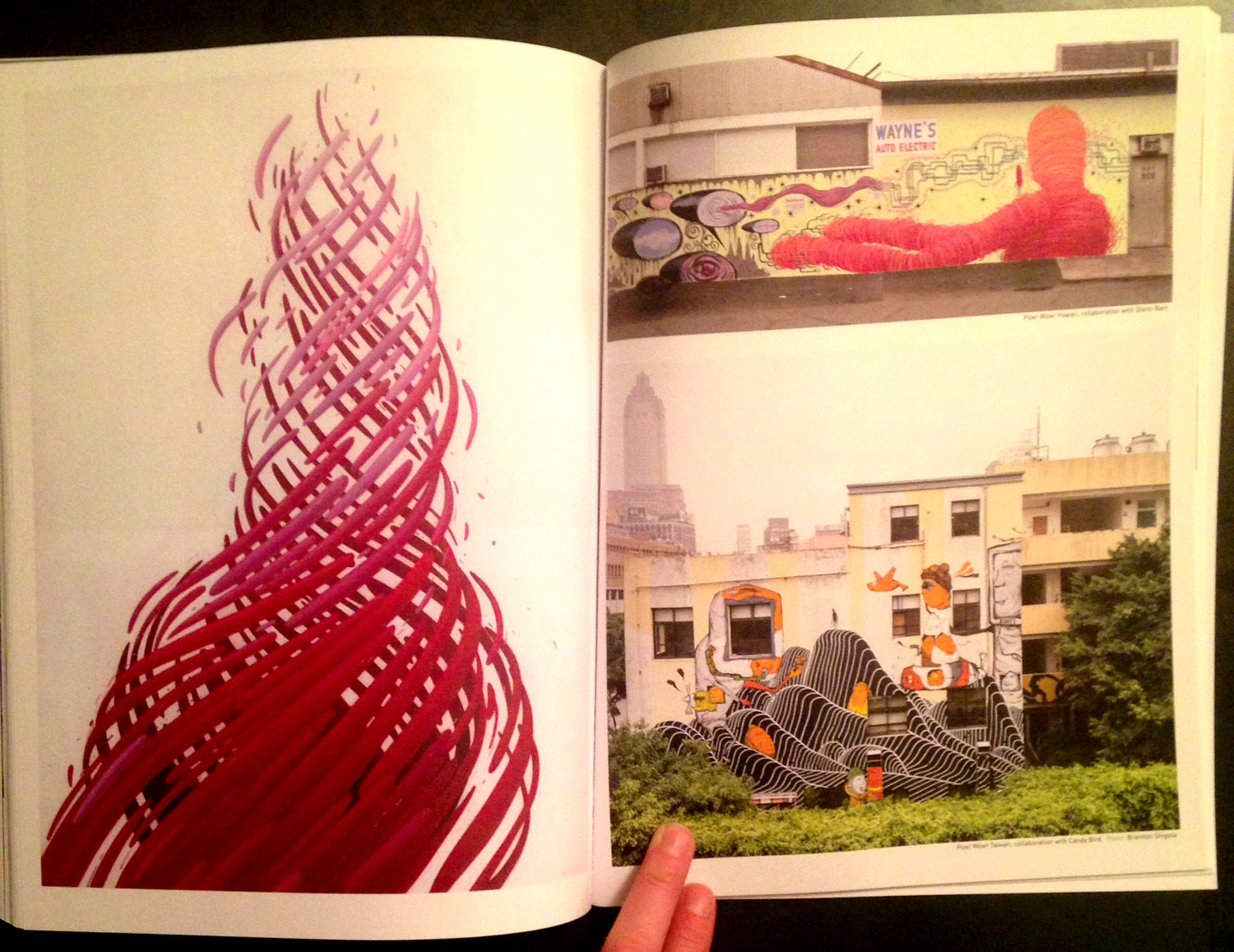

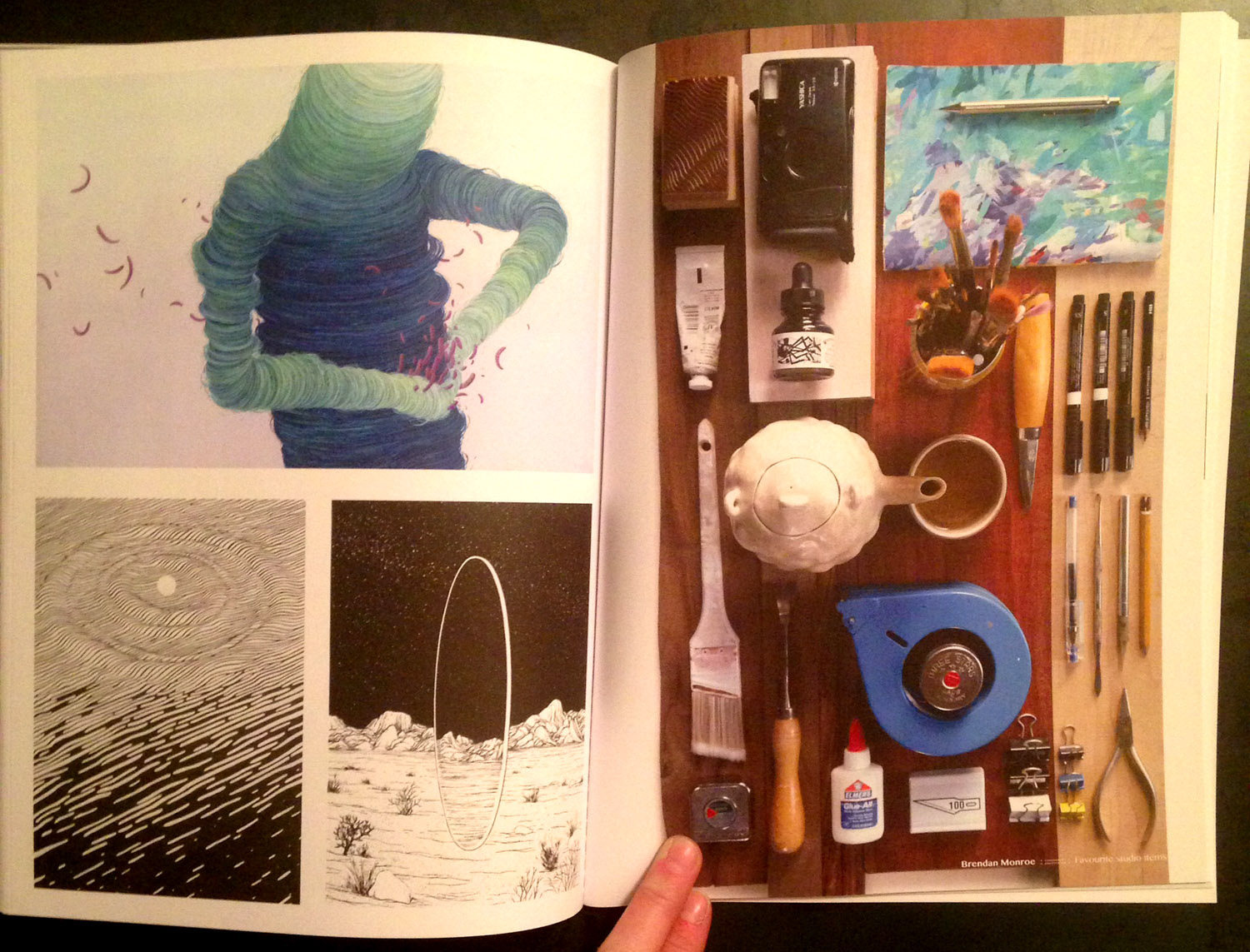

You also work in other mediums, including ceramics, papercuts and sewing soft creatures. How do you decide what to focus your attention on ?

Sometimes I need a break from drawing/painting. Other times specific ideas just come to me in a specific material like wood or porcelain. I love being able to move between two and three dimensional work – I feel like I am always learning new things that way. Sometimes it also helps me get out of a rut…for example with paper cuts I get a chance to focus on shape and composition more than my drawings which are so much based in line. I feel like I always need a place to play and experiment and changing materials now and then helps facilitate that.

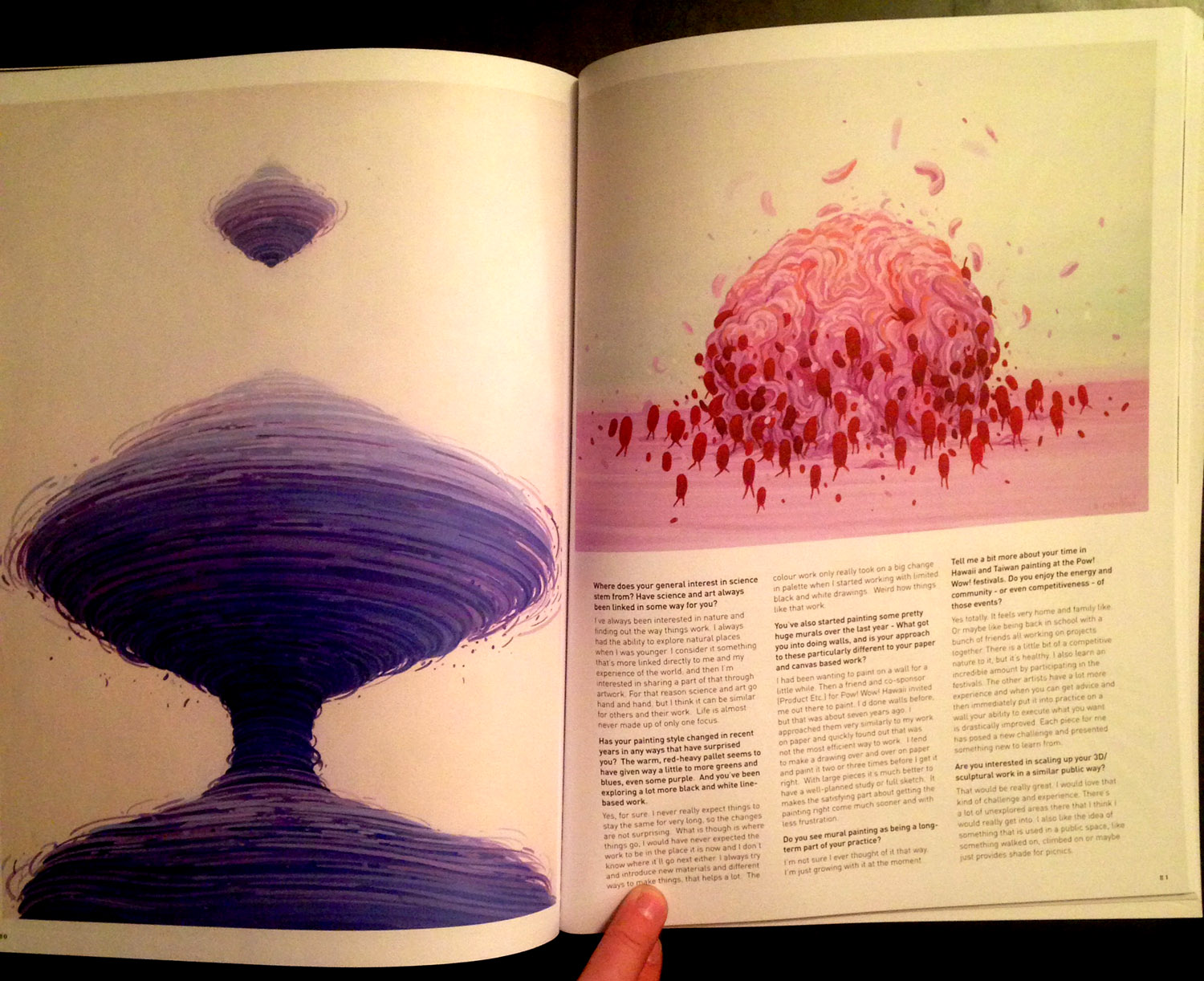

Often your figures engage with this strange landscape, & sometimes a shapeless mass that sometimes engulfs them. Can you talk about this inhuman presence?

A lot of that imagery comes from the idea of being overwhelmed. This could be a positive or negative thing depending on what’s in the mass and the perspective of the person within it. These masses started appearing in my work after I read a short story called “Parasite Planet” by Stanley Weinbaum that features some roaming cancerous masses called doughpots… More recently, for “The Planet of Doubt,” things have developed into more ephemeral forms that are like clouds or bunches of frog eggs. I like to think about being in nature as an observer, letting yourself be over taken… whether that is by a wave or a wind or fog or cold… just letting yourself be still within that. I am not very good at meditation (drawing and gardening are as close as I get to quieting my brain) ) In my new show I have a piece called “the Price of Stillness” where a woman has grown barnacles all over herself… This could be seen as an achievement in medication or a stagnation. I like that there is a duality that depends on the viewer’s perspective. One person’s gross out is another person’s idea of

bliss?

Your newest exhibition ‘ Planet of Doubt’ has a stunning 32 pieces in it. How do you manage to fit in time for making your work while raising a young daughter and working as a teacher? Do you have yourself on a schedule ?

Thank you. Ha, so there are actually 42 pieces! She couldn’t fit them all on the walls so a few are in the Galerie LJ flatfiles. I was on a roll apparently. When I did my last solo show with Galerie LJ Margot was an infant… I have to say it was much easier to work when she was younger, napping more, napping on me in a sling or carrier… I used to be able to nurse and draw at the same time! For this show I had to be more careful about planning my work time. I did a lot of late night studio sessions after M went to bed and even then there is always the possibility of being interrupted by a toddler’s need to pee or wanting Mama or getting woken up by sirens outside… I always lay there in my daughter’s bed when this is happening imagining my cat out in the studio licking my egg tempera palette. Two other big factors are: first, my husband has been taking the brunt of childcare while I have been working on this show – I really couldn’t have done this show without his help. And second: I was awarded a sabbatical for the last fall, so that time off allowed me to have more free studio time. I would like to say that I have myself on a schedule but even with the predictable routines you have with a small child (naps bedtime, etc.) there is still so much variation and you just have to roll with it. That is just part of being Mama. I work whenever I can and when I have a big deadline I inevitably will have to pull a few all nighters to make it work. I felt guilty for a while when she was even smaller… I was late to finish some stuff, I even missed some deadlines because she got sick and there’s just no way to get anything done when your kid has the flu or whatever. It is a hard balance to strike. Moms get a lot of shit, especially in academia. I actually had another woman artist say to me, when I was pregnant, “Gee I hope you don’t quit making art once you become a Mom” and another female colleague advised me to wait until I got tenure to get pregnant. I really try not to let it get to me anymore. I feel like this time in my kid’s life, where she is so small and needs me more intensely is limited… it is already flying by so quickly! So I am going to be present. And be late on some deadlines. And miss some shit. But I am not going to miss shit with my child. The rad thing about her being almost 3 now is we can actually draw together. That is so fun.

Your husband Jeremy Taylor is also an artist. What is it like to live with another artist ? Do you find that you inform each other’s work ?

I feel really lucky that I get to live with such an amazing artist! Jeremy’s work has had an influence on me since we first met. He is brilliant and thoughtful and his work is so so beautiful. I think I am his biggest fan! We have had some collaborative shows and those are always my favorite – the Handplant show we did at Cinders Gallery is still one of my favorite shows I have ever been a part of. We did so much porcelain and gold work for that one. Now that we have a kid we definitely have to coordinate alternate studio time better. Jeremy just spent a few months helping me while I finished my show so now its my turn to return the favor and help him finish some projects he has going on. We are also working on a duo show for April at AVA in Chattanooga, TN.

A lot of this newer work has the figures engaged in a kind of entanglement or trapping, dark forms halo their bodies, veil- like nets surround their heads and hands. Is this engagement a binding or did you have other things in mind?

It is a sort of binding, and depending on the drawing it is both menacing and/or comforting. I like the idea of binding being comforting though… if you think of it as surrounding and supporting something – like a sprained ankle. It seems restrictive but it’s actually allowing you to function. I was really interested with this body of work in themes of interacting with nature but also isolation, contemplation, and uncertainty.The Planet of Doubt story itself (where I got my show title) is set on a fog-covered planet being explored by two of Weinbaum’s recurring main characters (a married couple). Visibility is limited and immediately they deal with isolation, fear of the unknown, fear of being stuck, and not knowing how to interpret their surroundings/trust their senses. I found this story to be an interesting metaphor for dealing with chronic illness and anxiety. Of course in thinking about illness, I also started to think about healing, and spirituality. Specifically through creating personal rituals and communing with nature rather than spirituality via organized religion. So that binding could also be seen as a sort of conjuring or ritual for healing.