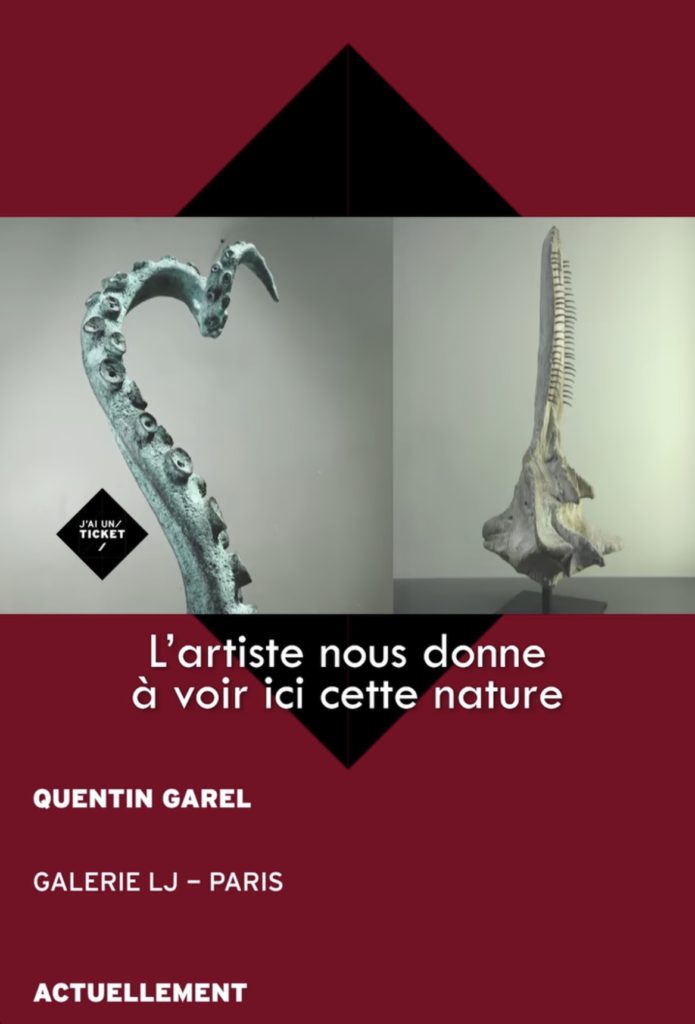

L’Octopus monumental au fusain de Quentin Garel, dans Côté Paris décembre 2021

By Amy Rosner | July 19, 2021

From now through July 22nd, Superchief Gallery NFT, the world’s first physical gallery space dedicated exclusively to NFT-based artwork, is hosting a solo exhibition for internationally renowned artist, Swoon.

Caledonia Curry, known professionally as Swoon, is widely considered the first women artist to break into the global street art scene.

Swoon’s solo exhibition is extremely significant to the NFT field at large. Female-identifying artists have been largely absent from the media discourse around cryptoart, despite their significant contributions to the crypto-verse and the field of digital art overall.

Entitled Cicada & Tymbal, the show will feature much of the same stop-motion imagery & animations from Swoon’s highly praised Cicada exhibition with Jeffrey Deitch, but this time, in NFT format.

This exhibition, which serves as Swoon’s debut solo outing with the gallery, takes the viewer on an immersive visual voyage into the artist’s personal history with works that intertwine images from memory and mythology to signify metamorphosis and healing.

The submergence and subsequent emergence of the cicada represent the personal transformation of the artist Swoon.

Swoon depicts vessels that contain the artist’s memories of childhood trauma stemming from a family environment marred by addiction and chaos.

“I think anytime you bring your humanity and personal experiences into your art, you create art that has a certain kind of truth to it. You create a situation where that truth can reach anyone, no matter how similar or dissimilar your experiences are. By being very specific, you gain a kind of depth, which makes it so that anybody can experience the work.”

Swoon credits New York and the creative process with saving her life. After a chaotic childhood in Florida, raised in an environment with parents in the throes of addiction, Swoon moved to New York to attend Pratt.

Her fascination with the city led her to break into the male-dominated world of street art.

When asked about any challenges she faced when emerging into this space, Swoon responded, “I didn’t find it to be very challenging. There was some anonymity at first, so nobody really knew who was doing what. It was almost like a blind audition, like when a concert pianist goes on an audition and the judges can’t see the gender of the person.”

“The street art community itself was really supportive. I actually find the top-of-the-art world to be way more sexist than street art. If you just look at the numbers of who is being collected by museums and whose work is at auction at different levels, you see a level of sexism that’s very intense. With street art, it’s treated more as a public open space and we were all doing it illegally. So it wasn’t about permission at all, it was just about doing things right.”

After confronting her trauma and learning more about the underlying issues that caused her parents to self-medicate, she chose to help others heal through her art and outreach and community-based projects.

In response to her choice to incorporate traumatic personal experiences into her work, Swoon answered, “For me it’s a choice between the emotional exhaustion of avoidance, and the emotional exhaustion of facing things. The emotional exhaustion of avoidance is perpetual and eternal, but the emotional exhaustion of facing things has a life cycle. So, I tend to choose the path that involves going directly towards things.”

Swoon works to help alleviate the suffering of other addicts, showing compassion and illuminating the tools to confront their trauma and begin the healing process.

Her imagery emanates the artist’s journey through the psychedelic therapy process in a style that recalls German expressionism.

“Every single generation, artists find a new tool and they figure out how to use it in their own way. It all goes back to the Renaissance with the invention of oil paint. New technologies change the way artists are able to do things. And that’s just what is happening here with NFT.”

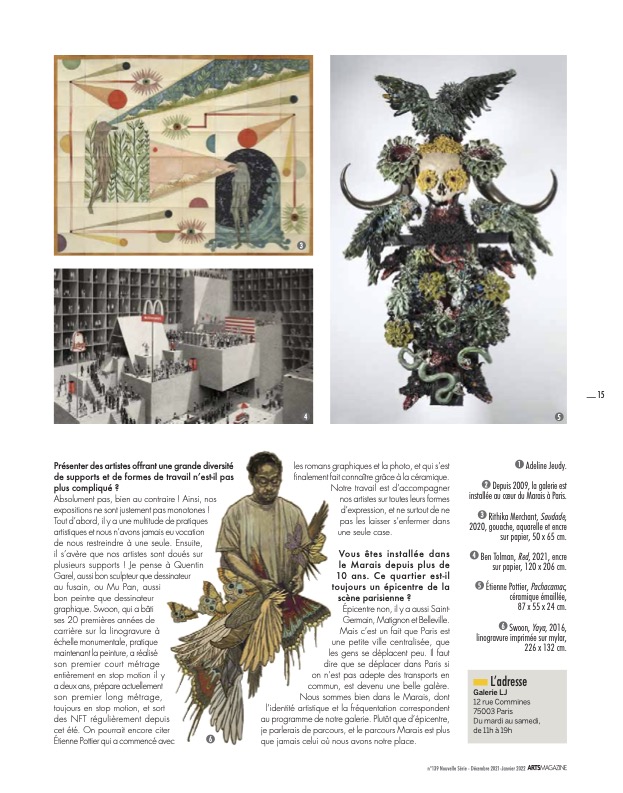

Saudade is the Portuguese word for ‘bitter-sweet’. It represents a deep nostalgia or melancholic longing for something or someone absent. Barcelona and Mumbai-based artist Rithika Merchant’s work Saudade shows two figures looking in opposite directions. “Two selves stand in conversation. One has returned from the future with a warning of the doom that lies ahead if we do not change our ways,” says Merchant, who was recently awarded the Vogue Hong Kong Women’s Art Prize at the 2021 Sovereign Asian Art Prize. Saudade won the highest marks from the jury for a woman artist out of 700 entries from Iran to Japan. “This piece evokes the bitter-sweet feeling my generation has when we think about the past and the future,” she says.

Saudade was part of an exhibition held in Mumbai earlier this year called ‘Birth of a New World’. While the exhibition was ostensibly about the

apocalyptic effects of climate change, its name alluded to a compelling conversation around the world. The Birth of the New World is a 360-foot bronze sculpture of Christopher Columbus located in Arecibo, Puerto Rico, which shows the explorer and his three ships traversing the Atlantic Ocean. Statues like this have been flashpoints in debates on imperialists who tortured, killed and enslaved hundreds of natives while amassing wealth. But there is also a contemporary debate on how imperialism and capitalism tie into the discourse on climate change: that a few rich people, countries and companies are destroying the planet.

Eruptions of fire

Merchant’s current show in Berlin focuses on feathered — or winged — women.

She draws on winged spirits, Peris, from Persian mythology. In the original myths, Peris were regarded as fallen angels who were denied entry into Paradise until they had repented. But Merchant’s winged women are shown leaping joyfully as they escape from a scene that appears idyllic at first glance but on closer look, shows small eruptions of fire beneath the delicate, blooming flowers. The paintings imply a freedom that exists beyond the confines of conventional perspectives.

Merchant’s interest in myths began when she read Joseph Campbell’s The Hero With a Thousand Faces. “I have always been very interested in narratives, myths and received histories. I am also interested in how these different fragments are woven together to form a complete image. Most cultures use imagery to tell stories and represent ideas. I try to use these ancient means of storytelling in a more contemporary context. Myth-making brings humanity back to the centre of concern, unlike science, which places humans as part of a greater scheme. Much as science gives an accurate description of humanity, it takes away the spiritual power given to every human to understand their own destiny,” she says.

Links to the past

Merchant’s work is filled with literary allusions, contemporary world events, international mythology, feminist references, botanical drawings and folk art. She uses symbols from epics — Greek, Indian, Portuguese — as well as folk art and science fiction to weave parallel narratives across societies to show links to our collective past.

Her fairly big paintings look familiar and exotic at once. The materials she uses, such as cut-paper collages, embroidery hoops, jute string, mother of pearl buttons, and other household materials, add to a sense of familiarity. “The whole tradition of craftmaking by women is to me a very powerful thing,” she says. “Incredibly talented women artists such as Leonora

Carrington and Remedios Varo used a lot of these materials and they were sort of brushed away as things that just women were interested in; but they made these profound paintings that made so much sense in the world then and now. There’s something powerful in reusing scraps to make something new. So I make my collages from scrap pieces I find around my studio, beating them, putting them together, and making this entirely new thing.”

Citizen of the world

‘Birth of a New World’, for example, used 27 paintings to tell a story about this point in history when climate change heralds an almost insurmountable challenge to the planet and the choices we have to make to save future generations. The exhibition took this conversation to its next logical step after the Anthropocene: rising water levels, space-travel, gateways to a different time, as well as Kalki bringing back a simpler, more optimistic age, ending the despairing Kali Yuga.

Merchant has seen both commercial and critical success since 2016 when French designer Natacha Ramsay-Levi saw her work on Instagram and invited her to design for the famous Paris brand Chloé. Merchant produced paintings filled with esoteric and spiritual symbols, as well as botanical images for Chloé’s summer 2018 collection. This collaboration earned her the Young Achiever of the Year at the Women of the Year 2018 Awards from Vogue.

Galerie LJ, Paris, showcased Merchant in spring 2019, first with a group show and then with a solo show in December 2019. Her next group exhibition will be held in Brussels in 2021, followed by a solo show in Paris in 2022. “Perhaps the very first detail that caught my eye was her use of colour, then almost immediately, the narrative aspect of her works and their composition. She is a great colourist,” says Galerie LJ founder Adeline Jeudy. “Her style is figurative, narrative. We could probably call her a graphic artist, because she works with lines, outlines and compositions, on paper. She often says in interviews that she is a citizen of the world and that’s true, you can see it in her work.”

The writer is the author of the fantasy series Weapons of Kalki, and an expert on South Asian art and culture.

Bravo à Rithika Merchant qui a gagné jeudi 10 juin 2021 le prix DDESSINPARIS – DDESSIN 21 ! Nous avons présenté son travail sur la foire Ddessin 21. Rithika gagne une résidence d’un mois à la Villa Ndar à Saint-Louis du Sénégal, et une de ses oeuvres rejoindra la Collection de Bueil & Ract-Madoux.

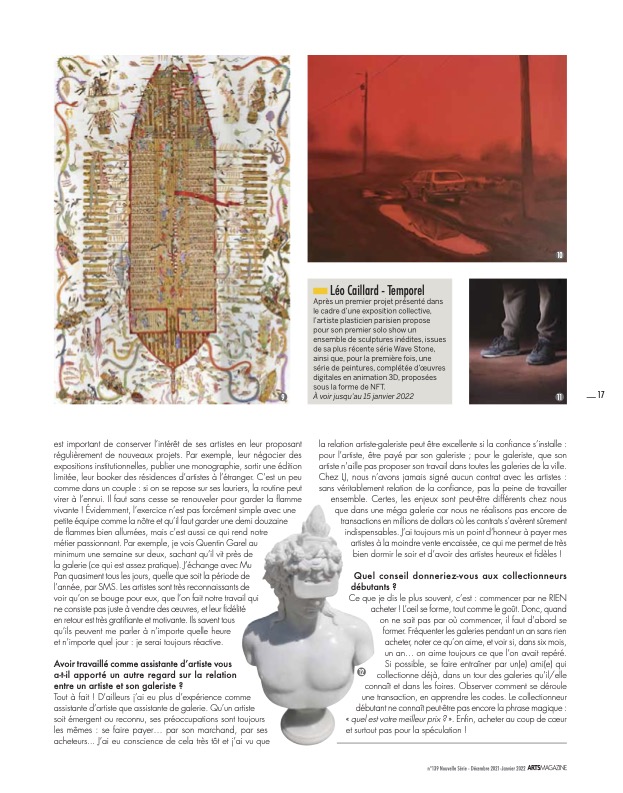

La première monographie de Ben Tolman, auto-éditée, est désormais disponible sur notre shop en ligne. Ce livre de 268 pages regroupe l’ensemble de son travail de 2014 à 2020.

Online store

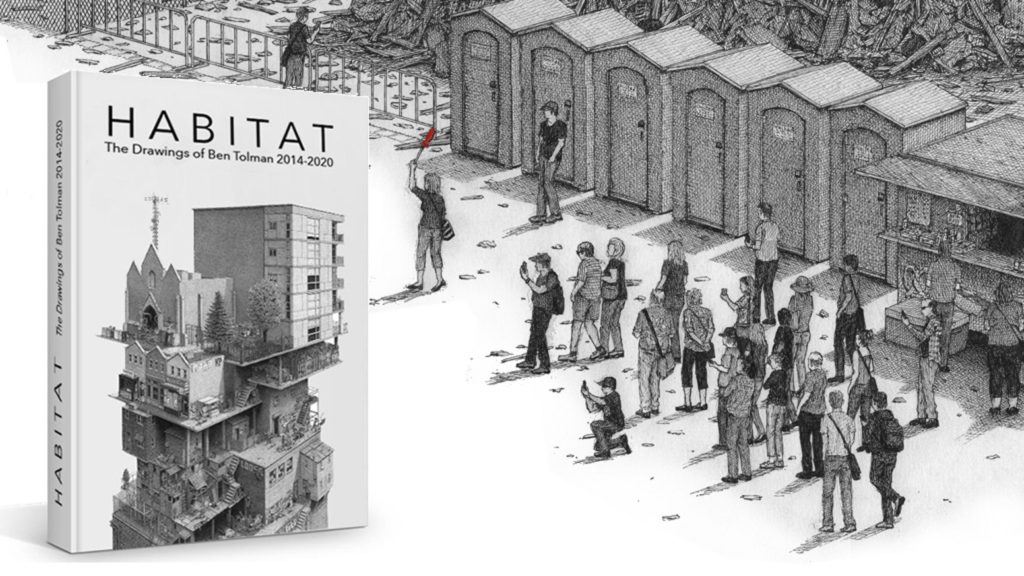

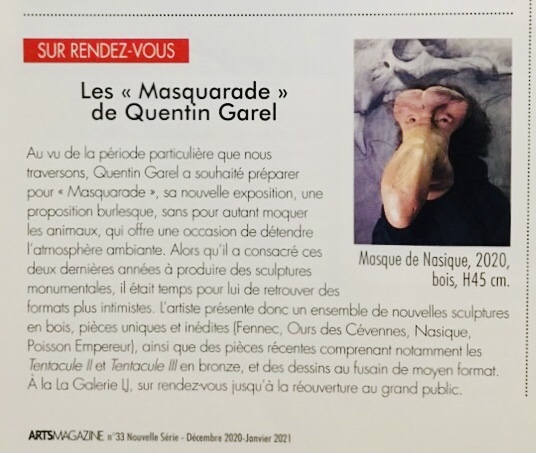

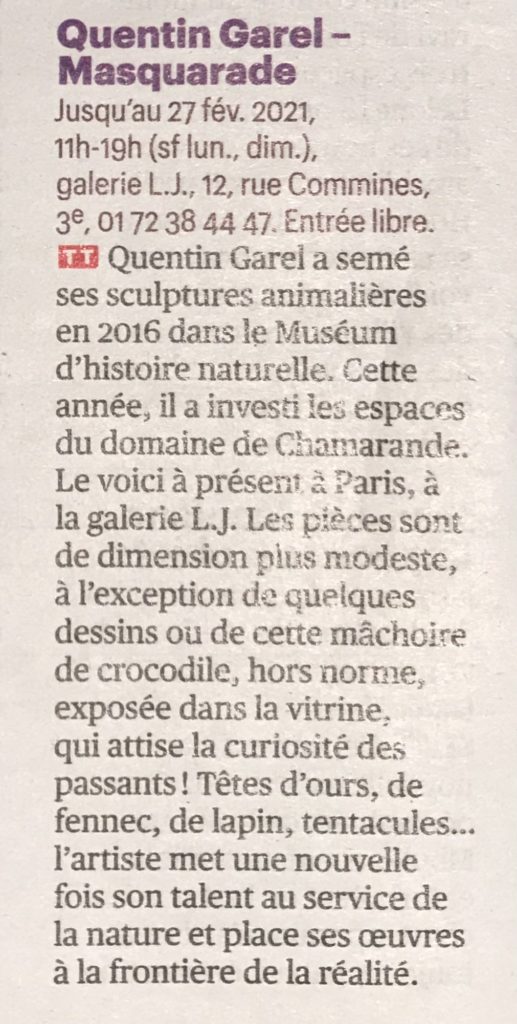

L’émission “J’ai un ticket” propose l’exposition “Masquarade” de Quentin Garel dans sa sélection de sorties culturelles hebdomadaire.

A voir à partir de 1:43 : https://www.6play.fr/j-ai-un-ticket-p_5246/jai-un-ticket-du-8-au-14-fevrier-2021-c_12836457

By CHRISTOPHER BORRELLI CHICAGO TRIBUNE |

DEC 08, 2020 AT 12:32 PM

(…) Speaking of pop art: “American Fried Rice: The Art of Mu Pan” (Abrams, $65) only looks like a study of ancient war murals. Look closer. This collection from the Taiwan-born prankster are remarkable bits of art mimicry slapped against cheesier shout-outs to “Star Wars,” Bruce Lee movies, fast food — the point being, high or low art, it’s all myth making. (…)

Email hello@galerielj.com

Tel +33 (0) 1 72 38 44 47

Adresse

32 bd du Général Jean Simon

75013 Paris, France

M(14) BNF

RER (C) BNF

T(3a) Avenue de France

Horaires d'ouverture

Du mardi au samedi

De 11h à 18h30