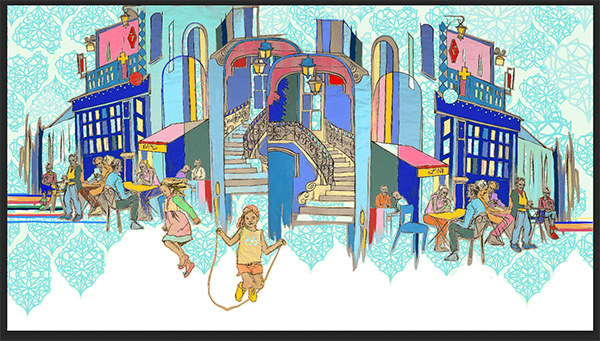

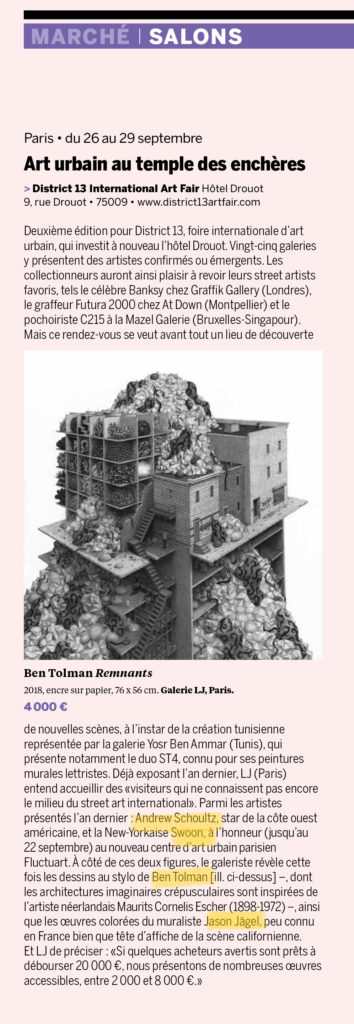

Notre stand à la foire District 13 dans Beaux Arts Magazine (janvier 2025)

On view everywhere on billboards in the city and the airports from July 17 thru the end of the Games in September. This project was curated by Nicolas Laugero Lasserre for Publicis Sport and was launched on July 11th, 2024, at Fluctuart, Paris.

By Amy Rosner | July 19, 2021

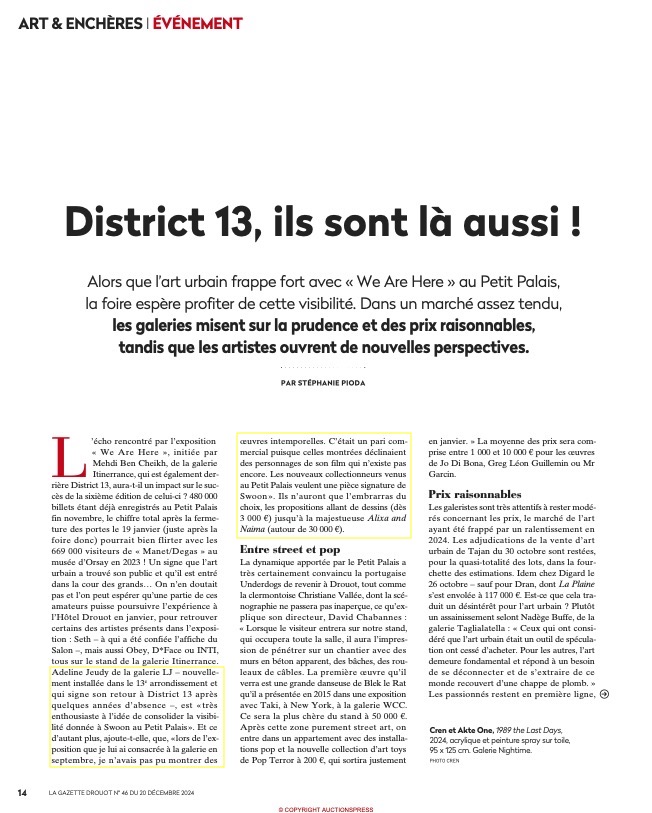

From now through July 22nd, Superchief Gallery NFT, the world’s first physical gallery space dedicated exclusively to NFT-based artwork, is hosting a solo exhibition for internationally renowned artist, Swoon.

Caledonia Curry, known professionally as Swoon, is widely considered the first women artist to break into the global street art scene.

Swoon’s solo exhibition is extremely significant to the NFT field at large. Female-identifying artists have been largely absent from the media discourse around cryptoart, despite their significant contributions to the crypto-verse and the field of digital art overall.

Entitled Cicada & Tymbal, the show will feature much of the same stop-motion imagery & animations from Swoon’s highly praised Cicada exhibition with Jeffrey Deitch, but this time, in NFT format.

This exhibition, which serves as Swoon’s debut solo outing with the gallery, takes the viewer on an immersive visual voyage into the artist’s personal history with works that intertwine images from memory and mythology to signify metamorphosis and healing.

The submergence and subsequent emergence of the cicada represent the personal transformation of the artist Swoon.

Swoon depicts vessels that contain the artist’s memories of childhood trauma stemming from a family environment marred by addiction and chaos.

“I think anytime you bring your humanity and personal experiences into your art, you create art that has a certain kind of truth to it. You create a situation where that truth can reach anyone, no matter how similar or dissimilar your experiences are. By being very specific, you gain a kind of depth, which makes it so that anybody can experience the work.”

Swoon credits New York and the creative process with saving her life. After a chaotic childhood in Florida, raised in an environment with parents in the throes of addiction, Swoon moved to New York to attend Pratt.

Her fascination with the city led her to break into the male-dominated world of street art.

When asked about any challenges she faced when emerging into this space, Swoon responded, “I didn’t find it to be very challenging. There was some anonymity at first, so nobody really knew who was doing what. It was almost like a blind audition, like when a concert pianist goes on an audition and the judges can’t see the gender of the person.”

“The street art community itself was really supportive. I actually find the top-of-the-art world to be way more sexist than street art. If you just look at the numbers of who is being collected by museums and whose work is at auction at different levels, you see a level of sexism that’s very intense. With street art, it’s treated more as a public open space and we were all doing it illegally. So it wasn’t about permission at all, it was just about doing things right.”

After confronting her trauma and learning more about the underlying issues that caused her parents to self-medicate, she chose to help others heal through her art and outreach and community-based projects.

In response to her choice to incorporate traumatic personal experiences into her work, Swoon answered, “For me it’s a choice between the emotional exhaustion of avoidance, and the emotional exhaustion of facing things. The emotional exhaustion of avoidance is perpetual and eternal, but the emotional exhaustion of facing things has a life cycle. So, I tend to choose the path that involves going directly towards things.”

Swoon works to help alleviate the suffering of other addicts, showing compassion and illuminating the tools to confront their trauma and begin the healing process.

Her imagery emanates the artist’s journey through the psychedelic therapy process in a style that recalls German expressionism.

“Every single generation, artists find a new tool and they figure out how to use it in their own way. It all goes back to the Renaissance with the invention of oil paint. New technologies change the way artists are able to do things. And that’s just what is happening here with NFT.”

After 20 years on the scene, the artist’s mythological creations evolve.

The artist known as Swoon sits at a sketch table in her Red Hook, Brooklyn studio, fiddling with a disembodied papier-mâché head.

“There’s nothing private,” she says, running a hand through her wild curls as I roam one of two rooms she rents in a labyrinthine artists-and-makers’ complex. Behind her hangs a large-scale mural depicting gritty but feminine myth-like scenes of motherhood. Smaller, ethereal cut-out portraits of women, many of them family and friends, are arranged in small clusters on the surrounding walls.

Because she hosted a party here recently, her studio is tidier than usual, she says, seemingly by way of apology.

The spaces Swoon creates are more often overflowing: Her recent show Cicada, at the Jeffrey Deitch gallery in New York, features a tangle of wire and cloth spilling out of the wall into a lush, overgrown swamp-like scene. Paper flowers and insects swarm a mer-like character, who cracks her ribs open to reveal snakes uncoiling from her heart. The fabric jumble appears to be gobbling up another figure, its limbs disappearing like moss-choked flotsam.

The recent body of work she’s been developing, beginning with Cicada, marks a new direction for Swoon. Injecting her characters with movement, she has adopted into her practice an entirely new medium she’s spent the past two years teaching herself: stop-motion film. Meanwhile, her visual language has taken on a more explicitly sinister and introspective tone, a departure for an artist who made her name beautifying the outside world.

Swoon, born Caledonia Curry in New London, Connecticut (she spent most of her childhood in Daytona Beach, Florida), began pasting her dreamy ink-block portraits on city walls in the late 1990s. Alongside peers like Shepard Fairey, Banksy and her good friend JR, she became central to a youth movement fueling street art’s ascent. Swoon was one of the few women to gain recognition in that world. Her bold, feminine murals, with nods to Greek mythology, soon captivated major museums and galleries, which she filled with immersive multimedia installations.

Her 2014 exhibit Submerged Motherlands shaded viewers under a paper tree that reached the height of the Brooklyn Museum’s 72-foot-tall rotunda. It was the museum’s first solo show dedicated to a living street artist.

From early on, Swoon saw art as a medium for activism, creating “spaces of wonder” that bring people together. In New Orleans, together with the New Orleans Airlift collective, she created a musical village whose ramshackle treehouses double as functioning instruments. With her community of punk artists and DIY craftspeople she famously built three rafts out of garbage and sailed them across the Adriatic Sea and into the Venice Biennale, uninvited. The renegade crew invited onlookers to join them onboard.

“Swoon’s practice is based in generosity,” says Anne Pasternak, the director of the Brooklyn Museum and a longtime champion of Swoon. “She wants to create dignified, humanistic, beautiful things about people, for people. She uplifts those who are less visible in our society, and she transforms the most banal and even devastated sites into places for real beauty.”

After the 2010 earthquake in Haiti, Swoon launched a decade-long project building colorful, disaster-resistant homes in the remote village of Cormiers. Having just finished the rafts, Swoon says, “I was working with a lot of artists and builders that knew how to confront exceptionally difficult situations and problem solve in unusual ways. I had an instinct that we could make that skillset useful.”

In Philadelphia’s Kensington neighborhood, which has one of the highest rates of opiate overdoses in the country, she leads an art therapy workshop for people in the throes of addiction. It’s a project she plans to grow in tandem with her outspoken efforts to combat the stigma surrounding addiction.

If there’s a thread that runs through Swoon’s diverse body of work, it’s “that idea that creativity can be a really powerful part of how you rebuild after disasters of any kind,” she says. “Social, physical, all different kinds.”

Swoon’s early life was colored by the chaos of her parents’ heroin addiction and struggles with mental illness. Forgiving them took years of therapy and meant reconciling memories of fear and trauma with memories of joy. “I literally thought my mom was going to kill me sometimes,” she says, describing a weeklong psychosis her mother experienced when Swoon was six. “And my mom would bake big zucchini bread and take me to art classes and be this wonderful person, and those two things are just true.”

That dual nature became a central refrain in Swoon’s work, the figure of “dark mother goddess” looming large in many of her installations. Partially autobiographical, her art was both an escape and a form of therapy.

“Almost whatever I’m doing, it’s going to be through art,” she says. “Am I thinking through a problem? It’s going to happen through art. Am I healing all these old wounds? It’s going to happen through art. Am I getting friends together? Art.”

In Cicada and in her growing body of stop-motion films, Swoon uses art to go inward, unearthing the trauma lodged in parts of her mind she hadn’t dared explore.

Behind the swamp-like installation that welcomes visitors to Cicada and an adjoining room filled with portraits of her friends is the show’s centerpiece: a small movie theater where a five-minute, semi-narrative reel brings Swoon’s characters to life.

The Brooklyn-based artist details the intersection of personal and global sustainability in her work.

June 26th 2019by Sarah Gooding

photos by Michael Lavine

This article appears in FLOOD 10. You can purchase the magazine here.

There have been times when art almost killed Caledonia Dance Curry, the multidisciplinary artist and activist known professionally as Swoon. In 2009, she and thirty friends were nearly run over by a barge while floating in ramshackle rafts from Slovenia to Venice. They had built them out of crates, plywood, and other junk rescued from construction sites and dumpsters across New York City. They sent the scraps in shipping crates to Europe, assembled them into twenty-foot-high floating islands, and set sail across the Adriatic Sea, uninvited, toward the Venice Biennale.

That project, titled Swimming Cities of Serenissima, was a comment on capitalist waste and excess, and it sparked a global conversation about recycling and radical self-reliance. It also cemented Curry’s already-legendary status as an artist.

“I never felt particularly successful as an environmental artist,” says Curry, perched on a chair in the middle of her warehouse studio in Red Hook, Brooklyn, not far from the Gowanus Canal, another body of water famed for its floating trash. Faces from her trademark life-size portraits peer out around us—on recycled wooden doors stacked against the walls, on sheets of brown paper hanging from the rafters, on a canvas placed on top of paint cans arranged on the floor. Each surface in the large industrial space has been employed as part of Curry’s artmaking process, but it isn’t a mess. Shelves housing containers of carving tools, string, glue, and other supplies are neatly organized with neon pink labels. As with the rafts, there’s a sense of order to the chaos.

photo by Tod Seelie

“We had a lot of aspirations on that raft trip, but I think we never felt that successful in terms of devising systems,” Curry admits. “In some ways it was great—we ended up producing very little waste, being in this self-created space. But I think that as an artist, you figure out where your strengths are.”

That project may not have gone exactly as Curry intended, but experimenting and pushing boundaries has always been her MO. Her career began twenty years ago with wheatpasted street art while she was a painting student at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn. Put off by the thought of creating art that would only hang in wealthy people’s homes, Curry started drawing, printing, cutting, and pasting portraits onto walls and surfaces throughout New York. The images were often made from recycled newspaper and were intended to decay over time—but they made a mark.

Curry’s wheatpastings secured the artist her first eponymous solo exhibition, curated by Jeffrey Deitch in 2005. Following that exhibit, her work was added to the permanent collections of the Museum of Modern Art and the Tate Modern, and she became the first living street artist to have a solo show at the Brooklyn Museum in 2014.

Titled Submerged Motherlands, this exhibition started out as a reflection on climate change and rising sea levels, having been commissioned not long after Hurricane Sandy devastated New York. But after the death of her mother from cancer following a long battle with opioid addiction, Curry found herself exploring more personal, maternal themes.

“I would say that’s one of the times when art saved my life,” she says. “When my mom was dying, it was one of those things where the only thing I could do while she was sick was draw a portrait of her. It felt like this little flagpole of sanity that you hold onto in a strong wind, and you’re like, ‘If I can just make work while this is happening, I can keep rooted to the earth.’” The resulting exhibition was both grounding and groundbreaking—its centerpiece was a sixty-foot tree that utilized the full height of the rotunda, a first for the Brooklyn Museum.

Curry has a way of not doing things by halves, sometimes to her detriment. In 2010, following the catastrophic magnitude 7.0 earthquake in Haiti, she and a group of artists, builders, architects, and engineers flew to the country to undertake a project called Konbit Shelter. It saw them build three sustainable houses, one community center, and start English and after-school programs—but they pushed themselves to the brink in achieving those things. “We didn’t know how long it would take, so we ended up cancelling our plane tickets, and we stayed until our health started to fall apart,” Curry recalls. “That was when we were all like, ‘You know what? Even if the final plaster isn’t finished, we’re going to have to leave. The rainy season is taking its toll, we’re working too hard, we’re working too long hours, and we’re just going to have to come back in the winter.’ It was one of those wake-up moments of like, ‘You have to take care of yourself.’ You can’t help others in crisis if you’re driving yourself into the ground.”

“Even though I very much love to harness creativity in service of social change, I also really believe that creativity needs a place to just be born raw.”

Following the death of both of her parents, Curry started to unpack the emotional toll that growing up around opioid addiction had on her. “Personal sustainability feels really big for me right now,” she says. “I found that I was coming from a place of real chaos and woundedness, as somebody who grew up [around] addiction, and just people who struggled a lot. The thing about harboring deep and repressed unconscious wounds is that it makes you do crazy shit. When I look at people who are hoarding so much wealth that they could never spend it in fifty lifetimes, and yet they’re still clear-cutting forests to get that palm oil and build their fortune, I’m like, something’shappening with that person. They’re scared of death, they’re trying to impress their father; there’s some deep psychological processes. If they could just confront the fear of death, if they could just confront the fact that their father is dead and is never going to approve of them, they wouldn’t have to do psychotic things that are harming the planet.”

Acknowledging and dealing with her trauma has enabled Curry to be more sympathetic to herself. She’s begun to take an increasingly measured approach to her work, which has expanded from her original wheatpasting to include a range of practices like performance, architectural installations, and community-building projects around the world. “I realized recently that I was constantly adding projects and I was doing, like, ten at a time, and finally I got to a point where I was like, ‘I can’t do them all simultaneously, I need to alternate a little bit.’ So I set down a bunch of my core practices, which were block printing, wheatpasting, and installation-making, and I put them on hiatus. Because if I didn’t, I wasn’t going to be able to teach myself new things.”

Curry’s work often has a purpose or practical application, whether it’s housing disaster victims, shedding light on climate change issues, or humanizing refugees. Throughout her career she has regularly blurred the line between art and activism—still, she views these things as fundamentally different. “Even though I very much love to harness creativity in service of social change, I also really believe that creativity needs a place to just be born raw,” Curry explains.

This renewed sense of self-sustainability and reckoning with her parents’ addictions inspired a recent project Curry undertook with Mural Arts Philadelphia. There, she hosted art therapy workshops at the Kensington Storefront, a community center in one of the areas that’s been hit hardest by the opioid crisis. The Storefront is a safe space where people can embrace creativity as a step toward healing—just as Curry has done herself. She acknowledges that these things may seem like small gestures, but for an issue that can feel insurmountable, it’s a step in the right direction.

Curry has addressed many overwhelming issues with her work, and is open about the challenges of achieving her lofty goals. She says the abandoned church she’s been trying to rebuild in Braddock, Pennsylvania as part of the Transformazium artist collective has been “a tough nut to crack.” With the collective, she was able to establish a separate company called Braddock Tiles, which “works with folks who are aging out of the Braddock Youth Program and teaches them soft skills so they can get jobs,” but they haven’t been able to transform the church into a fully functional community center just yet. “I discovered that me not living there has just not quite worked out,” she shrugs. “I’m actually looking to transition it. We’re talking to some folks locally, and my hope is to find somebody who’s doing work that’s about bringing up the community, who’s not just a gentrifying developer.”

She acknowledges that it’s important to know “when to call it, and be like, ‘Okay, this is bigger than me, I need help, I need to pass this on.’” Sometimes ending something can be as challenging as beginning it. When she made the decision a year ago to shift away from her primary art practices, she was scared—even though she realized that it was necessary for her personal growth. “Your processes become like a security blanket, and people know you for them, they like them, and they want you to keep doing them. So you feel like, ‘Oh my god, what’s going to happen?’” she laughs nervously. “But you just have to do it!”

She continues, “I feel like, over and over again, my creativity has led me to places that made me feel a little scared. When we first made the rafts, I was like, ‘Girl, what are you doing?’ You could make your creative life so easy right now, but instead you’re digging in dumpsters and living with thirty of your friends on a fucking raft! Like, why are you doing this?!’ But there was a part of my brain that was like, ‘I’m not listening!’”

Curry now incorporates ten-day silent meditations into her annual self-care ritual, along with three-month trips to Panama to surf and work on art away from the bustling city. Having grown up in Florida, she says surfing was a way of life. “When I was a baby, we’d spend months at a time living in some random place by the sea. We’d go to the beach every day, so I think it’s just in my blood. The ocean is my happy place.”

These days, downtime can feel like a luxury many cannot afford—but Curry learned the hard way how crucial taking a break can be. “I burned out a couple of years ago, and even though it sounds really decadent, I was like, ‘Oh, I’m going to Panama to go surfing for three months!’ It’s a matter of self-care, and it’s a matter of carving out time for primary creativity.”

“When I started giving talks about my family and addressing trauma and doing all these things, I was like, ‘I’m more scared doing this than I am being on a raft that’s breaking down in front of a barge!’ You know? There are different ways of facing your fears at different stages of your life.”

This change in mindset is reflected in her work. As she’s allowed more time for herself, she’s put more of herself into her art, from Submerged Motherlands to her most recent exhibition, Every Portrait Is a Vessel, at Treason Gallery in Seattle, where Curry gave a talk on the very personal inspiration behind the work’s exploration of trauma.

Now in her early forties, Curry can’t believe that she’s done some of the things she has. “Ten years ago I drove a motorcycle across India, and now I would never do that!” she admits. “Maybe I’m becoming a wimp.” She’s still doing things that scare her—she’s just being more emotionally vulnerable, as opposed to physically endangering herself. “When I started giving talks about my family and addressing trauma and doing all these things, I was like, ‘I’m more scared doing this than I am being on a raft that’s breaking down in front of a barge!’ You know? There are different ways of facing your fears at different stages of your life.”

Since her earliest wheat-pastings, her work has cultivated curiosity, and twenty years later that light hasn’t dimmed. Even when she’s confronting the darkest, most harrowing subjects, Curry radiates hope. It makes sense that her first name, Caledonia, means “steadfast or hard-footed.” It originates from an ancient Scottish tribe that fought off the Romans, she says.

She points to a portrait on the wall of a beautiful woman laughing. “That’s a young woman who had left the Syrian Civil War under extreme duress, as a refugee. Her family made their way to Sweden, and I was asked by folks there to help. Sweden had taken on 6 percent of its population in immigrants, and they were like, ‘We need artists who will help us with this moment of welcoming this new community.’ So I linked up with a friend of mine and she helped Maram tell her story, and I made this portrait and put it up in the museum,” she says, referring to Skissernas Museum in Lund, Sweden.

“I was thinking, ‘This woman has been through tragedy that most of us will never even imagine.’ Society is at a place where it’s struggling, but when I look at the news and the images that we’re seeing of people like Maram, it’s 100 percent focused on distress. And the situation is distressing, but if you look at somebody and you’re only ever seeing them in distress, you’re seeing them in a one-dimensional way, so you can’t see the whole of their humanity. I was like, ‘You know what? Maram is in this beautiful town now, she’s starting a new life, let me show a different side of her! Let’s see that she’s actually a normal teenager and she just wants to be happy like everybody else.’ So it was a conscious choice for me to draw her in this really celebratory moment, to show that there’s more to her life than the suffering that she’s been through.”

If there’s a key to solving any of the issues Curry has come up against throughout her career, it’s empathy—whether we are looking inward or at someone else. “I think that people who are in that frame of mind will, in the long run, be making a more sustainable world,” she smiles. “I hope so, anyway!” FL

Email hello@galerielj.com

Tel +33 (0) 1 72 38 44 47

Adresse

32 bd du Général Jean Simon

75013 Paris, France

M(14) BNF

RER (C) BNF

T(3a) Avenue de France

Horaires d'ouverture

Du mardi au samedi

De 11h à 18h30